Spotlight on Michigan State University’s Creativity in the Time of COVID-19

Anuj Vaidya, IA Communications Director.

On a brisk morning in early October 2024, I boarded a flight to East Lansing, Michigan to attend a conference – Creativity in the Time of Covid – that was the culmination of a three-year project organized by Digital Humanities and Literary Cognition Lab (which is co-led by one of the project leads, Prof. Natalie Phillips) at IA member Michigan State University. The project documented how everyday people used creativity to cope with the pandemic by crowdsourcing contributions, undertaking public humanities collaborations, and highlighting art as a tool for combating inequity and injustice.

I had been invited to present at this conference by my friends at HIVES, a research workshop led by graduate students Michael Stokes and Jessica Stokes, which seeks to create a generative space for conversations at the intersections of disability studies and animal studies in popular culture. My own workshop Love, Simeon: Cross-Cutting Viral Vectors Between HIV and COVID, shone a spotlight on the non-humans (specifically primates) laboring for human health. As I stumbled into my hotel room exhausted after a full day of travel I was daunted by the prospect of having to wake up early and prepare myself for a full day of intellectual stimulation and camaraderie. As rewarding as that would be, I was also acutely aware of the effects of exhaustion and overstimulation on my post-Covid psyche.

As I opened up the schedule to review the plan for the next two days and prepare myself, I was surprised and delighted to learn that the conference sessions would only begin at 2pm. I had the entire morning to wake up and restore myself, prepare for my presentation without feeling rushed, and have lunch with other conference presenters, which would allow me to show up with all my spoons! I would later learn, in my conversations with Jessica and Michael, that the schedule was intentionally crafted this way to allow for crip time and capacity. While slow scholarship is something that we often aspire to, the conference organizers had worked with HIVES and a group of undergraduate students to prioritize crip methods throughout the conference.

“The Creativity in the Time of COVID-19 project gathered art and creativity more broadly from those most impacted by COVID including disabled people. To ensure the art was accessible to the people who created it and to as many people as possible, the project sought the involvement of organizations committed to accessibility in the arts. HIVES, with our commitment to access as belonging, was happy to consult on this project. We had the pleasure of mentoring brilliant disabled undergraduate students committed to imagining accessibility in the every day and in more expansive and aspirational ways. Undergraduate researchers on the project created events and exhibitions grounded in the tenets of disability justice. They developed collaborative methods for drafting image descriptions to make the creative expressions accessible to blind and low vision people both at the exhibitions and beyond them in the accessible online database where this work will live on.”

– Jessica and Michael Stokes, HIVES

Beyond the spacious scheduling, this meant that every session was enriched using CART (Communication Access Real-Time Translation) and ASL (American Sign Language). Image descriptions and access scripts were requested of all participants, and multiple spaces (all within walking/rolling distance of one another) and diverse modes of engagement were provided, to make events inclusive and accessible across a range of dis/abilities. A low-stimulation space was made available to all conference participants who needed to retreat and recharge, and a designated community art room with multiple arts activities (which doubled as the conference canteen) allowed for participants to engage in community building through arts and crafts when they needed a break from panels and presentations.

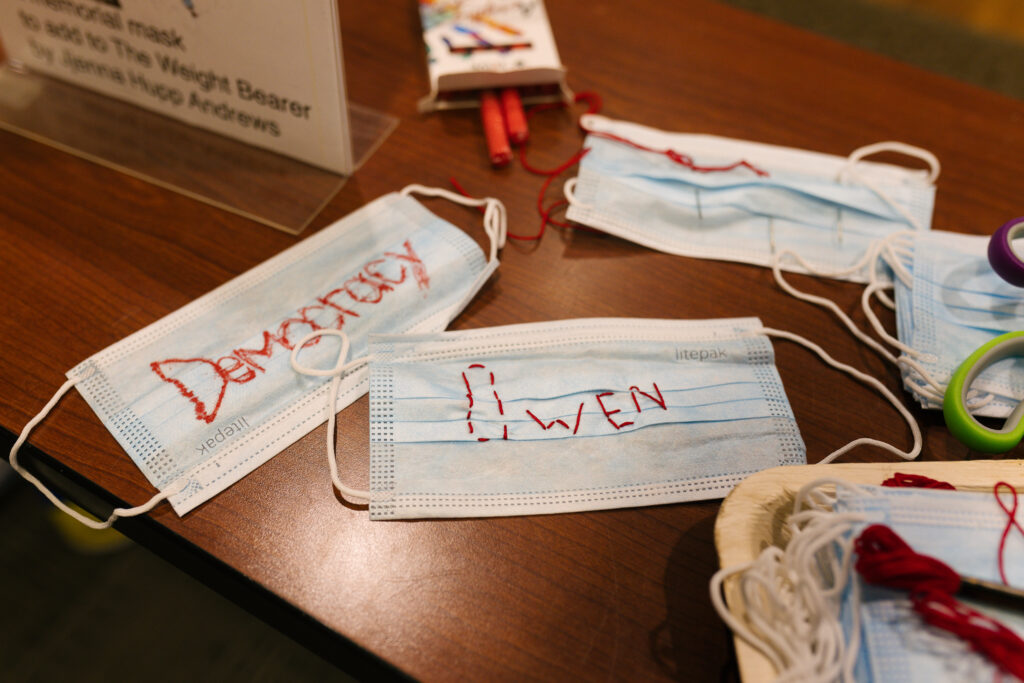

Some of the most engaging and intimate conversations I participated in took place around these arts activities, which involved making origami butterflies with AgeAlive artist Zahrah Resh, or sewing memorial masks for Jjena Hupp Andrews’ powerful installation which was an homage to the labor of first responders. These projects showcased the power of artistic creation and expression in coping with the trials and traumas wrought by Covid, and the importance of joy and remembrance in dealing with the aftermath of the pandemic: the whimsy of origami butterflies adorning the heads of conference participants made us smile, and the weight of the memorial masks made us resolve never to forget. These activities also foregrounded the importance of community and collaboration, which are the cornerstones of disability justice, and the primary strategies that allowed us to traverse the taxing terrain of the coronavirus pandemic.

“In our exhibition for “Creativity in the Time of Covid-19,” we wanted to emphasize the power of art to provide an therapeutic outlet for processing, for healing, for rage…and for community. Creating this archive of pandemic art and stories over Zoom served as our team’s way of holding onto community and mental health during the hardest phases of Covid-19. We wanted our conference to show how community-engaged art and scholarship could feel as the days’ events were co-created by speakers, artists, and audiences together.”

– Natalie Phillips

A deep attention to collaboration and process was also on display in the panels and presentations at the conference. Sessions not only featured panelists who presented on how they had used the arts and creativity to build community and foster conversation throughout the pandemic, but also revealed the process of pulling together this three year project that took an enormous amount of faculty, graduate, and undergraduate labor. It was empowering to see students presenting alongside invited guests, and the nitty-gritty process (from grant-writing to logistics) foregrounded alongside artistic and scholarly content. This attention to process was as refreshing as it was educational, reminding us all of the enormous amount of care, creativity, and collaborative labor that went into surviving the ravages of Covid.

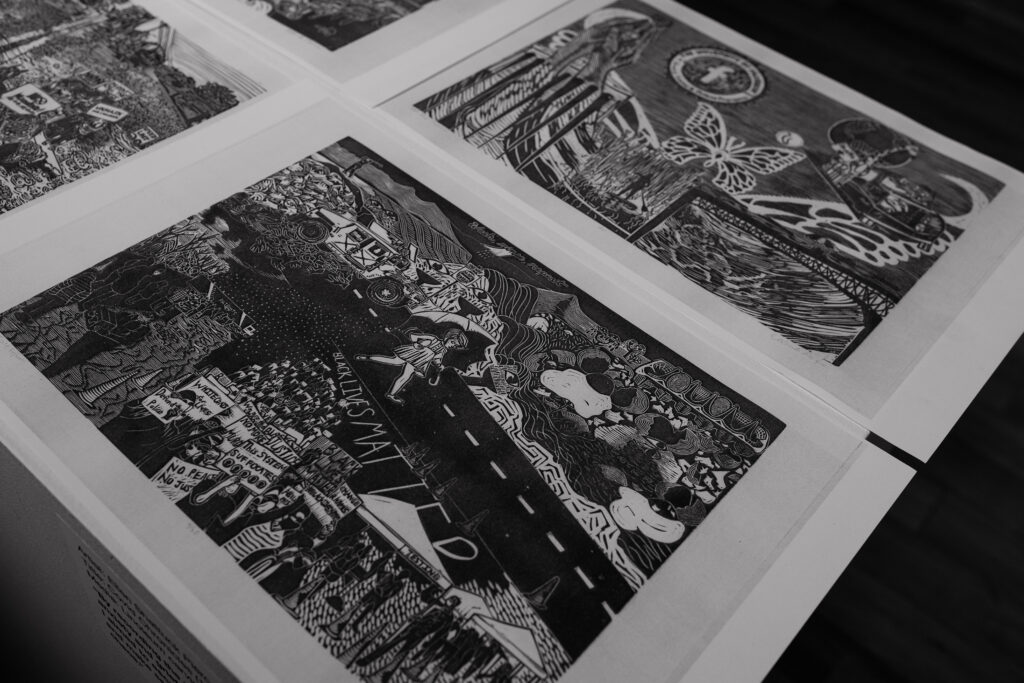

Another aspect of the conference beyond the presentations and keynotes was an art exhibition which was spread out across two galleries, one on campus (METROSpace) and one at a community venue (Look!Out), which presented a selection from the 2,000+ artworks that were crowd-sourced through the three years of the project. These selections focused on intersectional artists, particularly from BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and disability communities, and showcased works from across the world, reminding us of the trans-national nature of the pandemic. Alongside the art was a plethora of printed material in English and in Korean (as one of the project leads, Soohyun Cho, was located in South Korea through the lockdown), featuring writing, comics, artworks, stickers, postcards, and zines (including the ongoing HIVES publication buzzine). The sheer breath of formats and stories was staggering, and offered a fascinating window into the multitude of ways that individuals sought to use creative expression both as a way to cope with the challenges of isolation and loss, and to celebrate the resilience of the human spirit. I barely managed to scratch the surface of this archive during my visit, which can be accessed online at: https://creativityandcovid19.org/s/ctc-19/page/welcome

“Starting from a local collection at Michigan State, we were delighted and amazed that our project went global, gathering over 2,000 creative examples from 16 countries. During one of our conference trips to Seoul, I was excited to be able to interview and collect pandemic art from six South Korean artists, which included paintings, collage books, documentary film, and more. I’m struck by both the shared experiences and cultural specificity of creativity during this crisis—underscoring why it’s so crucial to record pandemic history and preserve an archive of these works. In capturing these works in our digital archive, we invite scholars, students, and the public to explore the socio-political and cultural contexts that shaped pandemic art.”

– Soohyun Cho

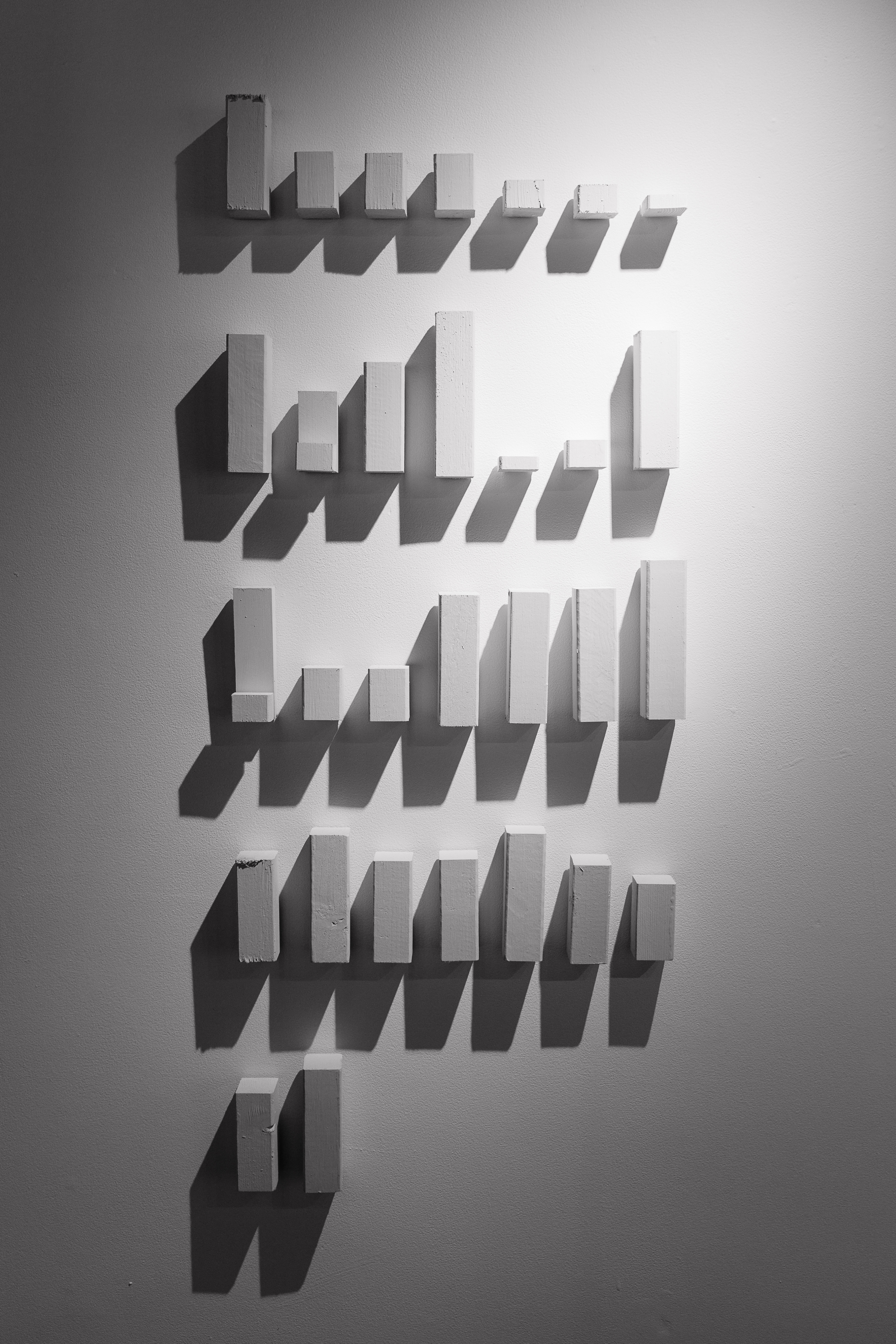

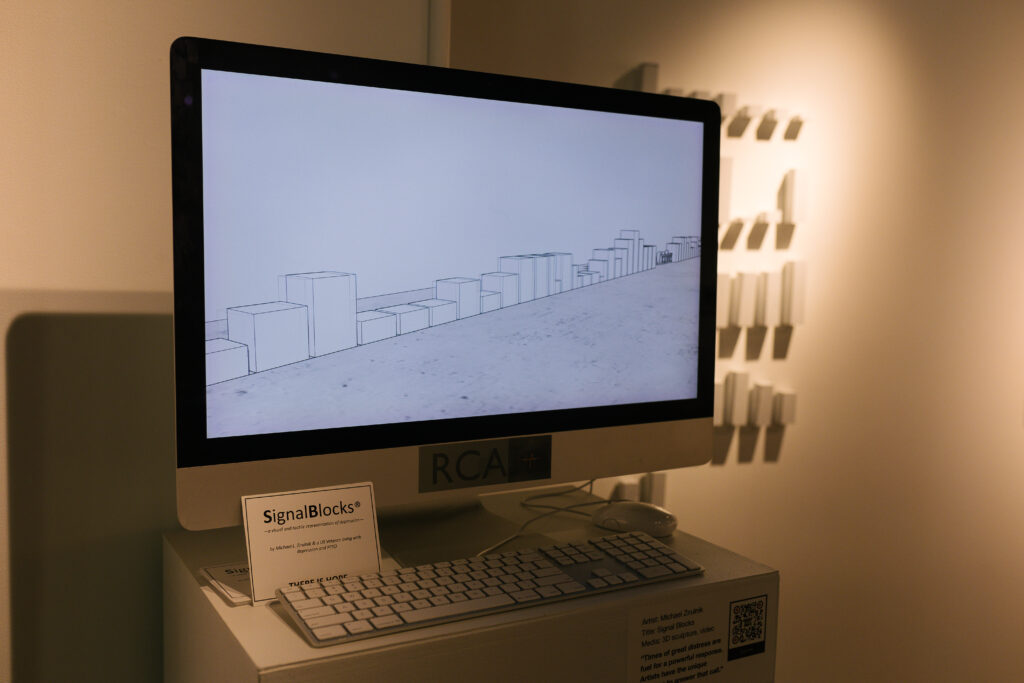

One of the more ingenious access strategies that I encountered was the inclusion of numerous instances of haptic art as part of the exhibitions. While braille catalogs and descriptions provided access to information, the haptic element allowed blind and visually impaired participants to directly engage the artwork through touch. For instance, Shattuck Ellen Pierce’s Covid Chronicles, a series of 16 linocut prints that documented the artist’s personal experiences as a mother and an art teacher during the chaos of the pandemic, lent themselves to such a treatment for the linoleum prints are created through relief carving. For the exhibit, the prints were mounted on the wall, while haptic prototypes were made available for hands-on sensory engagement. Another was Michael Zirulnik’s powerful project SignalBlocks, which captured the emotional terrain of a US war veteran on a scale of 1-10 (1 signalling attempted suicide, and 10 signalling bliss) over the period of a year. While Zirulnik had previously exhibited this work as a public art sculpture that attendees could walk through, in this haptic version he transformed the fiberglass blocks into wooden blocks that were scaled to one’s hands. By running one’s fingers over the work, which was mounted on the wall as a 3D sculpture, one could literally feel the highs and lows experienced by his collaborator.

Georgina Kleege, professor emeritus from UC Berkeley who delivered the keynote that evening, reminded us that sight engages just one organ of the human body – the eyes. It is possible to experience touch, however, through numerous parts of the body, each offering us a different sensory experience. Think how different the touch of hands versus the tongue or the bottom of your feet is! Given the range of this haptic experience, Prof. Kleege (who is blind) proposed to the gathering that it was not she who was visually-challenged, but rather we who were sight-dependent (to the detriment of the other senses), in the process losing out on the sensory richness of the body in its encounter with the world. Prof. Kleege has been on a mission to encourage museums to open their art collections to the public for touching. But there is a lot of resistance to this idea, she says, especially given that art collections are also economic investments. They have been receptive to the idea of haptic interpretation, where she becomes a haptic-proxy for the audience, interpreting the artwork through her finely tuned sense of touch.

As I returned home from the conference, energized from two days of expansive and inspirational learning, hands-on art-making, and new friends and community connections, I reflected on the power of the imagination which had transformed the trials of the pandemic into a forest of creativity. It required an enormous amount of time and effort, collective organizing and labor, and a commitment to community-engaged art and public scholarship that centered marginalized voices/experiences and foregrounded grief as much as joy. As a project from the IA network, it offers a great model for how we might survive the trials that are forthcoming across America today and in the future.

Photo Credits: Michelle Lippert and Soohyun Cho