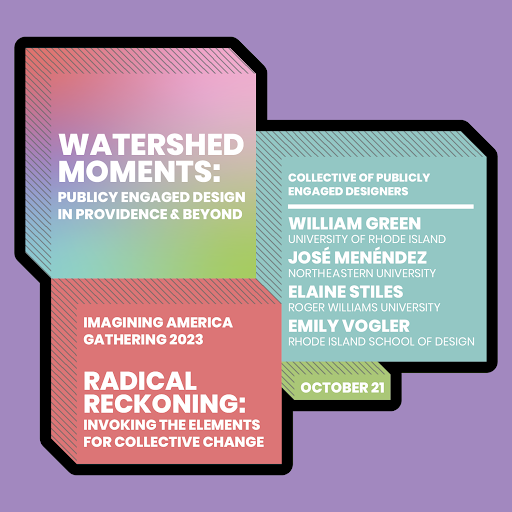

Watershed Moments: Publicly Engaged Design Education in Providence and Beyond

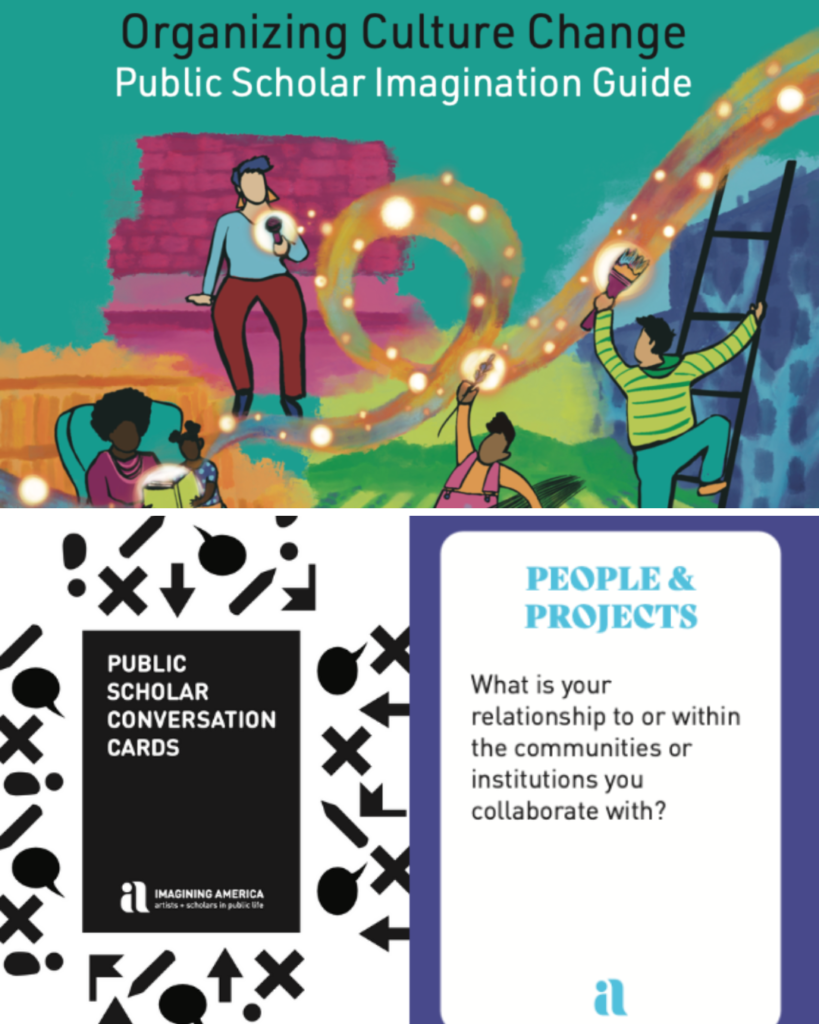

The CoPED Session at the 2023 Imagining America National Gathering, Providence RI

Presenters:

William Green, José R. Menéndez, Elaine Stiles, Emily Vogler

Organized by:

Mallika Bose, Brett Snyder, Langston Hay, Guadalupe Alvarez

How do Providence based designers grapple with a variety of uncomfortable truths (such as harm created by their institutions) while at the same time support community engaged activities with positive results? CoPED (Collective of Publicly Engaged Designers) held a roundtable discussion and workshop at the 2023 Imagining America Gathering featuring four Rhode Island based scholar / practitioners each involved with publicly engaged design from a variety of perspectives.

Panelists reflected on the theme of Radical Reckoning by asking how we confront uncomfortable truths and how we develop and sustain projects that bridge campus and community. Panelists included William Green (University of Rhode Island), José R Menéndez (Northeastern University), Elaine Stiles (Roger Williams University), and Emily Vogler (Rhode Island School of Design or RISD). Collectively, their work tackles issues of access, urbanization, climate change, open source tools, racial and environmental justice, developing inclusive narratives, and the critical roles students play in investigating, instigating and sustaining meaningful conversations. During this session, we discussed potential pitfalls of publicly engaged design and teaching and shared best practices within the field.

Elaine Stiles, Roger Williams University

The Co-Lab: The RWU Public Humanities and Arts Collaborative

Elaine Stiles, as the faculty director of the Co-Lab at Roger Williams University, presented their innovative work in public humanities and arts. The Co-Lab focuses on community-driven projects to bring forward inclusive narratives and histories of marginalized populations. Stiles highlighted their emphasis on areas like visual and performing arts, cultural studies, digital storytelling, and the development of a new Public Humanities and Arts curriculum at RWU. A key project she discussed was ‘ReVision’, which maps and acknowledges disappeared communities and spaces and erased pasts. Additionally, she shared her approach to teaching centered on intersectionality and cultural responsiveness, aiding design and landscape architecture students to connect empathetically with local communities.

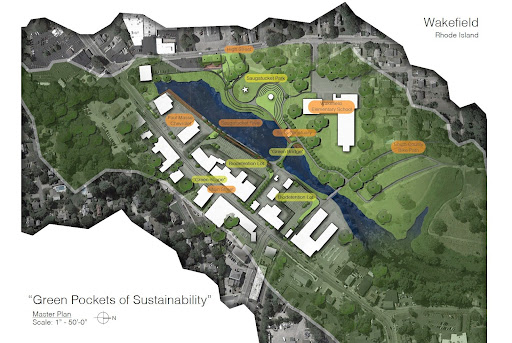

William Green, University of Rhode Island

How landscape architecture design studios engage and inform communities

In his presentation with Imagining America, William Green provided a portal into his endeavors within design studios and how these opportunities allow students to create meaningful contributions to public initiatives. These ventures allow students to gain professional skills and experience, be involved within the community, placing them in an environment where they can tease out important conversations as well as create visualizations that are essential in the development of these projects. This community involvement revolves around different activities ranging from workshops to games, with the goal of getting the viewpoints and opinions of the local community. Will also acknowledged a set of challenges they have had to deal with throughout this journey, such as community-engaged studios taking more time than traditional studios, finding a common ground within different work schedule times among the residents, and raising money to support their projects.

José R. Menéndez, Northeastern University

Community Building Through Graphic Design Initiatives

Jose Menendez’s presentation centered on his work with Buena Grafica Social Studio and their approach to community building through graphic design. Founded with his partner Tatiana Gomez, Menendez described how their studio engages communities through print and environmental graphics. He showcased examples like social justice posters given freely to the community, materials promoting civic engagement and voting, and works celebrating Latin American identity. Menendez highlighted Buena Grafica’s collaboration with the Rhode Island Department of Health in producing Spanish language posters about vaccinations and opioid overdose. Menendez discussed detailed designing visual strategies for education, and his work creating educational posters on permanent display at Providence Preparatory Charter School. He also touched on graphic interventions in public space, citing the studio’s contribution to the visual identity of 195 District Park in Providence. Also featured was their work with the Providence Storm Water Innovation Center, focusing on creating informative graphics about environmental issues and water systems. Central to their mission is the amplification of Latinx art and design, demonstrating Buena Grafica’s dedication to visually empowering and connecting communities.

Emily Vogler, Rhode Island School of Design

The Dam Atlas

Emily Vogler’s presentation centered around the Dam Atlas, a comprehensive tool designed to provide insights into dams in New England, particularly aging ones earmarked for potential removal. She delved into the dual aspects influencing this consideration: the impact of dams on local sense of place and the community’s feeling of exclusion from the dam removal process. Vogler emphasized the critical need for public involvement in decisions surrounding river and water management, reflecting on how these decisions intersect with communal stewardship of local resources. The Dam Atlas project, she explained, is an endeavor to forge new social practices, aiming to bring local communities together. This initiative seeks to facilitate community engagement in decision-making about dam removal, encouraging residents to contemplate divergent viewpoints and consider how their values, beliefs, and actions are intertwined with their environment and sociocultural identity.

Workshop and Reflections

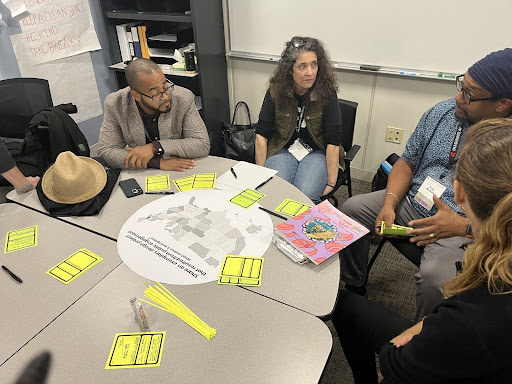

Formative to the session were a set of questions that emerged out of discussions with the presenters that both touched on the theme of the Imagining America Gathering (titled, Radical Reckoning: Invoking the Elements for Collective Change), while also weaving together the various modes of community engagement of the individual presenters.

After hearing from the presenters, participants were invited to reflect on the presented work in relation to their own experiences with publicly engaged design at three workshop stations. Each workshop station provided an opportunity for critical engagement and response.

Questions and reflections that emerged from the workshops included:

Workshop Prompt 1:

Share examples of exemplary publicly engaged design work that you know of. Where are these projects located? Who were the stakeholders involved? What issue was tackled?

We learned about new public engaged design projects across the country such as:The Venice Arts organization in Los Angeles that provides arts based education for low-income families, the Clio in Kansas City that increases access to Latin-x history and culture in Kansas, as well as projects in Providence such as the recently constructed Pedestrian Bridge and Community Park that includes programmable space allowing community ownership, as well as the Tomaquag Museum that aims to build understanding of the Indigenous People of the Dawnland and to take action to promote equity.

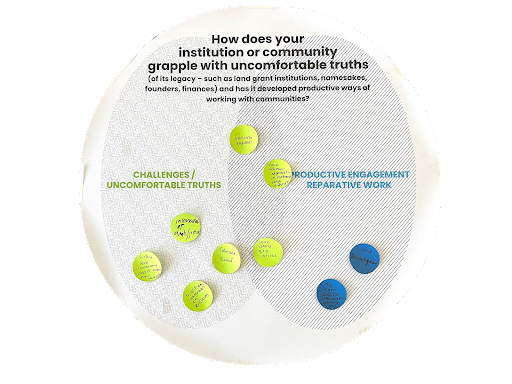

Workshop Prompt 2:

How does your institution grapple with uncomfortable truths (of its legacy – such as land grant institutions, namesakes, founders, finances) and has it developed productive ways of working with communities?

This proved to be one of the most difficult questions to answer with each answer prompting another question. The topic of land acknowledgments being merely performative prompted questions of how to deal in more meaningful ways with contested space. This was discussed as the intersection of good words and bad actions. One particularly poignant example of uncomfortable truth lies in Roger Williams (the namesake of one of the colleges being represented, who on the one hand had utopian ideals treating indigenous people as equals while on the other was ultimately complicit in the slave trade. These uncomfortable truths, however are the basis of a particular class: The Roger Seminar that asks students to respond to the past by interrogating it. (see: https://www.rwu.edu/news/news-archive/roger-seminar-first-year-rwu-students-react-past)

Workshop Prompt 3:

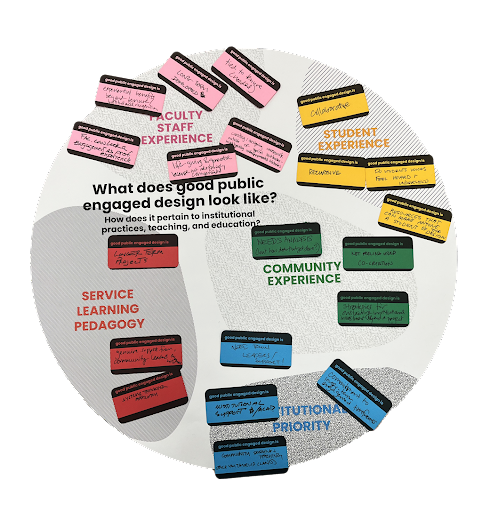

What does good public engaged design look like? How does it pertain to institutional practices, teaching, and education?

We divided best practices into several categories based on student experience, community experience, service learning, institutional priority, and faculty staff experience. Within each of these categories, the question was simple: what does good publicly engaged design look like?

In looking over these responses, a few takeaways were evident. First, the priorities under each of these groups was quite different, often based on the needs of each of these groups (for example, from community members, that childcare needs are met, or that meetings are at convenient times). This underscores the point that successful publicly engaged design is dynamic, complex and requires trust amongst stakeholders.

A second takeaway is that there needs to be some alignment and understanding between these different perspectives (for example, relative to expectations of work that students are capable of doing or that if a meeting runs over dinnertime that there will need to be funding to cover food/refreshments).

A last takeaway is that publicly engaged design offers the chance to rewrite histories and consider which groups were ignored, rendered invisible, and left out of the planning process and to be intentional about who is involved.

Zooming out to the presentations and workshops as a whole, it was also clear that publicly engaged design can take many forms and can inform public space and community narratives in meaningful ways. While there were many challenges that pervaded projects, there was a common theme of intentionality that bridged projects that tackled issues at different scales from graphics, infrastructure, or hidden histories — but that meaningful publicly engaged design done in thoughtful ways can lead to positive change no matter the scale or medium.