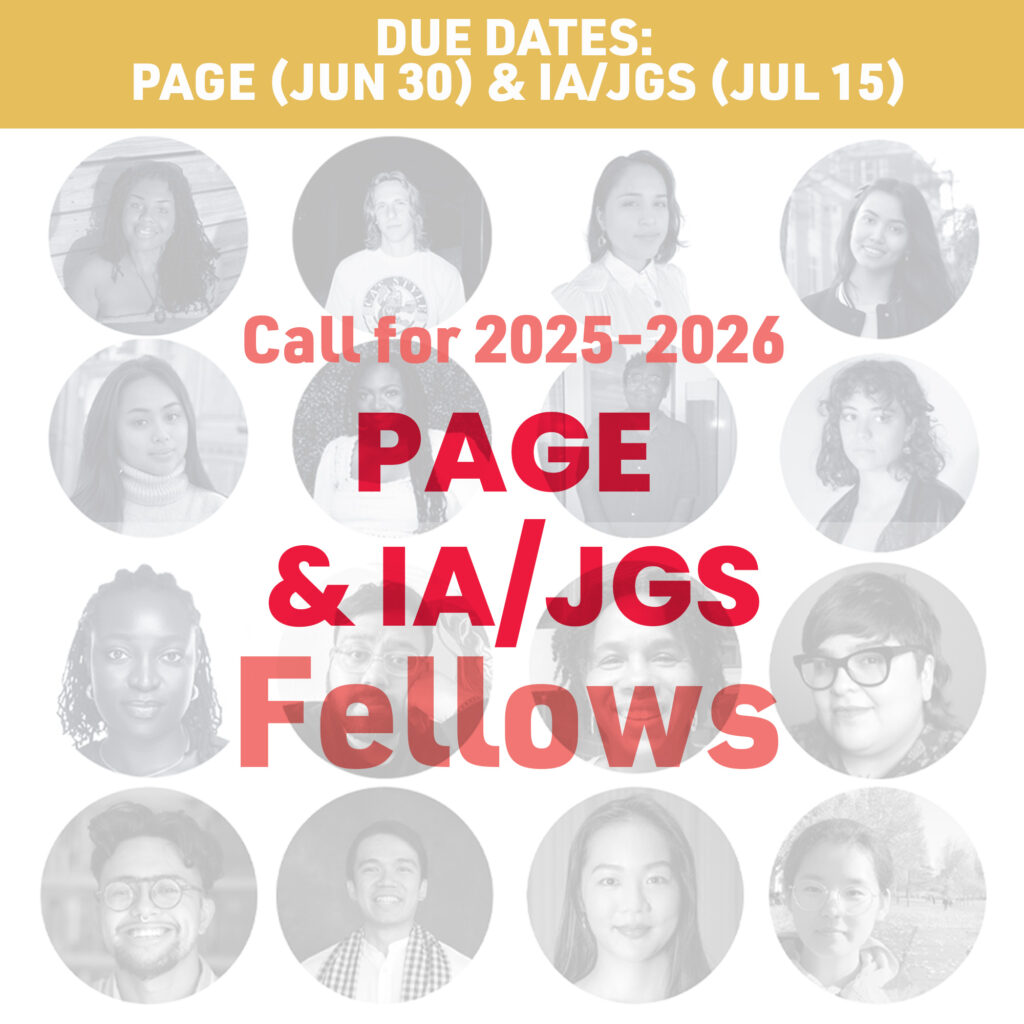

I Am Who I Say I Am: Reclaiming Native American Identity through Visual Sovereignty

Writing and Photography by Haley Rains (Muscogee Creek)

Feature Image description: Jace Naki’e (Numu [Northern Paiute] / Newe [Western Shoshone] / Hopi [Tobacco Clan]), Sacramento, CA.

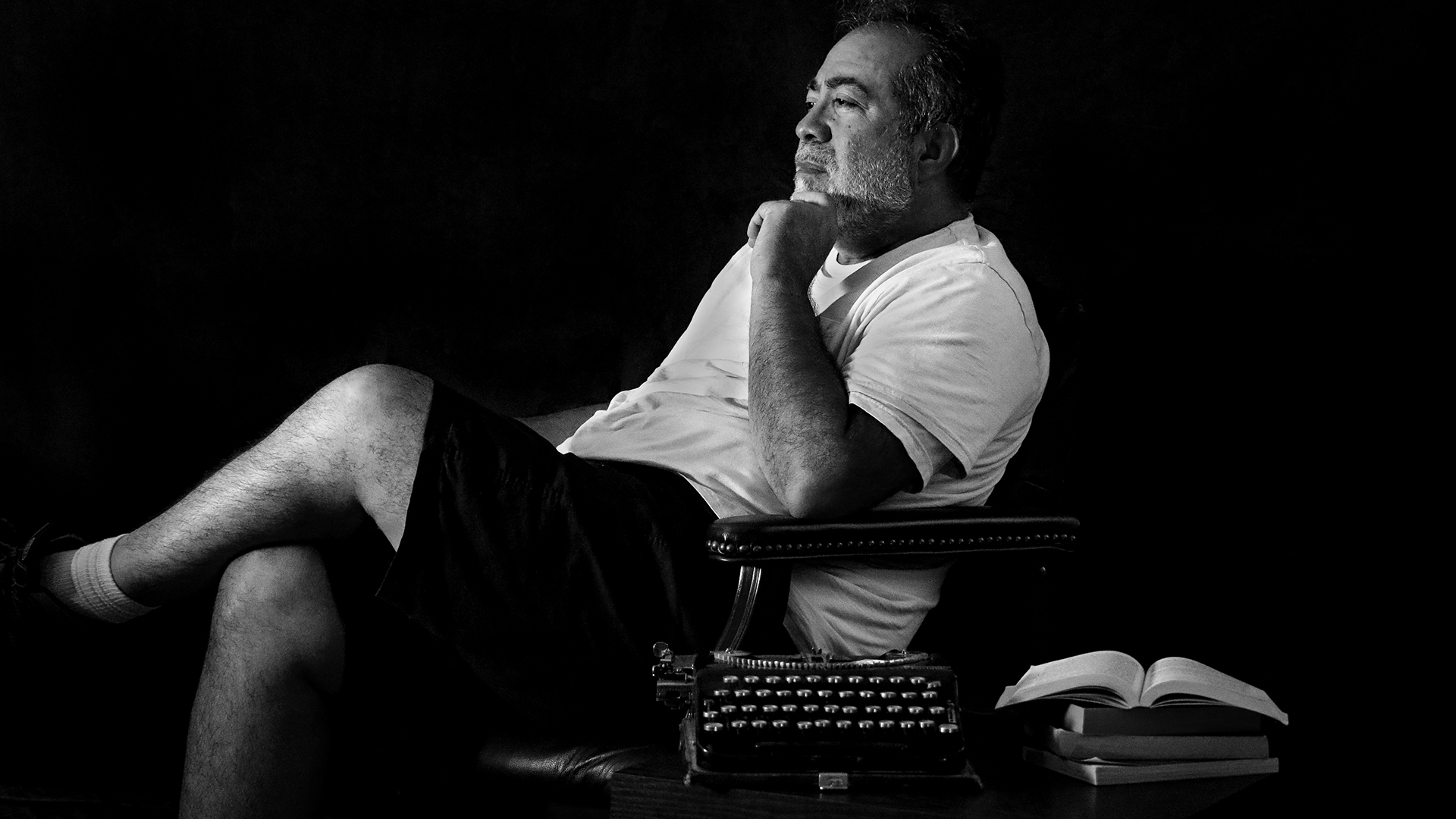

The Maori filmmaker Merata Mita once said, “I’ve always felt strongly that our land gets taken, the fisheries and forests get taken, and in the same category is our stories. What we see on the screen is only the dominant, white, mono-cultural perspective on life… We need to see our own people up there. We need to be able to identify with our own race. We need to see each other up there, and we need to go out and do it.”

One of the greatest tragedies that Native American people have experienced — and continue to experience — is the silencing of our voices as a result of others speaking for us. This exclusionary practice severely diminishes our ability to control our own narratives.

In my publicly engaged scholarship, I engage in the practice of Visual Sovereignty, which can be defined as exercising the inherent power to govern oneself and control one’s own narrative (and the narrative of one’s people) via self-representation in film, media, performance, and photography.

For many Native American individuals, daily life hardly resembles that depicted in media and popular culture. When depicting Native Americans in media and popular culture, non-Natives present American Indians as savages, “vanishing” Indians, and impediments to American progress. These representations have established a model for depicting Native Americans, one which has become the standard for how non-Native Americans view indigenous people: horse-riding, feather-wearing, tee-pee-dwelling, mystical people of wild, unconquered territories.

In my public scholarship, I push back against inaccurate, oversimplified depictions of American Indians by non-Native filmmakers and in doing so, empower Native American people by helping them reclaim their indigenous identities.

By depicting Native American people in a more nuanced light, I show non-Native American audiences more multifaceted — more human — portrayals of Native American people, while also providing an opportunity for Native American audiences to identify with the complicated, layered characters we see on screen and in photographs — a privilege, historically, we have been denied.

By engaging in Visual Sovereignty, by way of publicly engaged scholarship, I bring new perspectives to America’s vision of Native American people — especially those located in the

American West — by giving a voice to the Native American experience.

Art, film, performance, and other forms of media are exceptionally influential components of any society; they reflect our customs, values, beliefs, histories, and the narratives by which we ascribe importance, determine power, and relegate certain populations to the margins of society. The stories we tell and the art we create reflect our interpretation of the world around us.

That is why it is critically important that Native American people are afforded the space within which we are free to express our own values, experiences, and identities and, subsequently, position them to be received — and celebrated — by American and global society.

I believe that asserting one’s right to self-definition by visually expressing one’s own experiences is a basic human right; therefore, publicly engaged scholarship that seeks to accurately represent Native American people and their diverse experiences contributes to empowerment and full participation of Native Americans in contemporary society.