Rituals of Repair: Rethinking Practices of Community Engaged Design

On October 14th, 2022, CoPED presented, “Rituals of Repair: Rethinking Practices of Community Engaged Design” at the Imagining America National Gathering. This event, co-hosted with The Small Center, the Tulane School of Architecture’s community Design Center and SCAPE reflected on rituals of repair and renewal. The discussion used, as a premise, considerations that designers might have before, during, and after a publicly engaged design project.

To initiate this session, the Small Center and SCAPE each presented one project, which was then followed by a workshop style exercise during which participants (which included a broad array of designers, planners, organizational and city leaders, as well as community members) spent time reflecting on their own practices.

The Small Center (represented by Ann Yoachim), an academic initiative associated with Tulane School of Architecture, presented one of their projects, Parasite Park, a community led skatepark on the outskirts of New Orleans. In presenting the project, the Small Center laid out their own design process, which begins with seeking out ideas generated by the community. The expertise that The Small Center brings, ranges from knowledge around permitting, funding, and community engagement, to navigating the process of potentially years long projects.

SCAPE (represented by Sophie Riedel and Jennifer Schecter) presented the Chattahoochee River Project — a sprawling 125-mile continuous trail that connects 19 cities, involves 7 counties, and includes over 1 million residents within a 15-minute bike ride. Sophie and Jennifer presented their expertise across multiple fields and showcased their engagement process that was able (over the approximately two year design process) to lead or help facilitate over 80 public engagement events that reached 700 people in person and more than 5000 online. Events ranged from workshops, to presenting at neighborhood meetings, to events that decentered the design team, to youth engagement events such as the “River Ramble.”

Following the two presentations, each prompt (before, during, and after) acted as a springboard both to consider the presenters’ projects as well as those done by workshop attendees.

Before

The first prompt, “Before” asked participants to consider the parameters one might consider as they select a project in the first place. The wide range of comments were illustrative of the deep understanding of publicly engaged design/planning in the workshop group.

A first set of responses coalesced around thinking about some of the necessary elements that are required to pursue a project in the first place. As Ann (from the Small Center) presented in the workshop — all of their projects are actually initiated through public comments and suggestions. In publicly engaged work it is imperative that the project team develop an authentic understanding of the history of the place, which often involves decades of systemic violence. This points to the need to know not only what has worked previously, but more importantly what has failed and why they failed.

Such a process, not only improves the outcomes, but leads to relationship building, establishing trust with and amongst stakeholders and promotes an environment for honest and hard conversations.

Successful publicly engaged work needs to be based on an ethics of care and an epistemological stance that local knowledge is valid and valuable. Such work needs to commit to consistency, value the lived experiences of community stakeholders and involve the widest range of stakeholders.

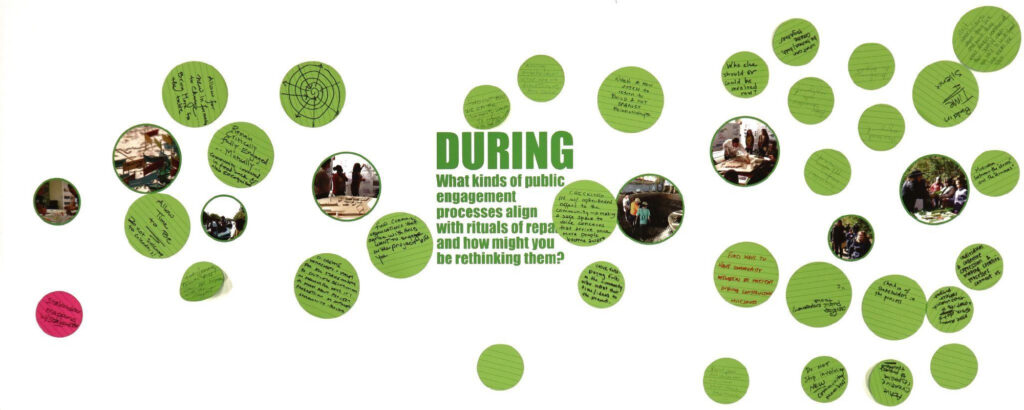

During

The “During” prompt asked participants to think about What kinds of public engagement processes align with rituals of repair and how they might be rethinking them? Rich conversations revolving around this question generated many comments. They range from reflecting on the very meaning of community engagement as well as suggestions and reminders during the process. Above all, a general and overarching insight pointed to the importance of place-based engagements. It is rooted in the importance of contextualizing the process with local knowledge. There was consensus that the community’s needs, desires, and attitudes should be prioritized.

According to the reflections, the process of engaged community projects is usually spiral, iterative, and back and forth. Therefore, community-engaged work needs to allow flexibility and accept that it does not always stick to calendars and original plans. A project’s ultimate outcome may involve much adaptation and adjustment during the process. This also involves the effort made during community engagement to mediate between the doers and the dreamers.

During the process of community-engaged work, professionals need to find out and confirm IF and HOW the community wants to be engaged with the project. Then, community work needs to make efforts to ensure openness throughout the process. It has to be open and encouraging to new and unanticipated information and changes. Professionals need to provide open-ended and safe places and conversations that facilitate individual and collective expressions, especially in voicing their concerns. Moreover, community-engaged projects need to find ways to involve and welcome new community members throughout the process. One tip addressed is that during community work, professionals have to check in with stakeholders and ask if anything and anyone that should be included has been left out and forgotten on the table.

Stakeholder collaboration and relationship building are recursive in the event. Our participants point to the significance of cultivating stakeholder relations using meaningful or creative ways (such as stakeholder mapping and co-creation workshops and spaces). They view relationship building as a crucial part of continuous community-making. Comments also address the importance of connection during and possibly beyond the completion of the project. Comments remind us to think about the ideal timing, frequency, and ways to return to the community to sustain but also not exhaust the relationships.

Comments highlight the potential subjects that should be involved, such as community talents, youth, and community organizations. Conversations on acknowledging and encouraging community talents and community organizations willing to engage in projects. Youth engagement is elevated as an approach to foster stewardship. In the shoes of community members, there are conversations to remind us that community-engaged projects need to value the contribution of the community members. Paying community members for their contributed time and intelligence is highlighted, but it also reveals the challenges to doing so in the practices.

The process of community-engaged work stresses the importance and ways to check in with stakeholders during the project. Reminders on de-catering the designers imply critical reflection of the roles played by designers in defining the work. The project needs to serve the community, not only the designers.

Lastly, the conversation also raised some practical concerns and suggestions. For instance, one comment recommends that professionals visit where stakeholders live and work to observe and investigate how they use space because, in reality, community members may not communicate their spatial needs. One comment points to the relatively participation-insufficient phase – during construction, it points to the need to have community members be present during critical construction milestones.

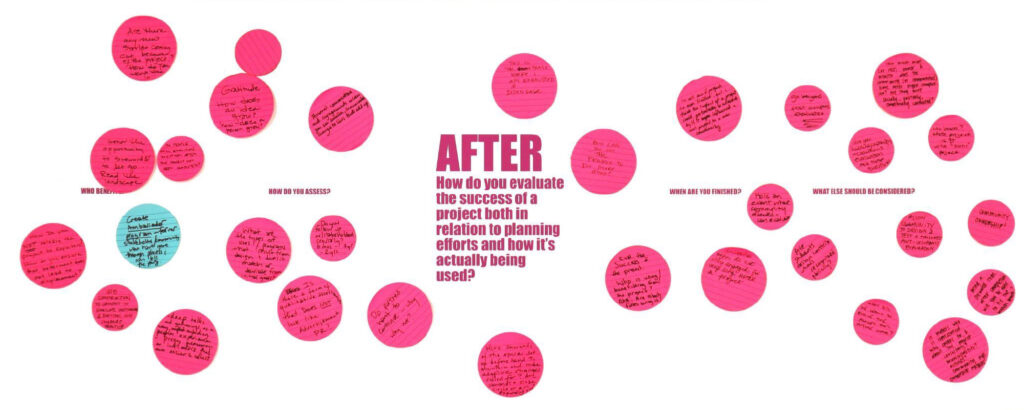

After

The “After” question asked participants to evaluate the success of a project in relation to its planning efforts and how the project is actually being used. This question solicited a wide range of comments, ranging from affirmative declarations (“How can you use this project to do more good?) to constructive suggestions (“Allow the community to design and test a tailored post occupancy evaluation.”).

A first series of responses addressed the topic of who ultimately benefits from a project. Concern was expressed to ensure that “betterment does not lead to displacement.” Also, by looking at who continues to promote a project (the community, municipalities, universities, developers, community organizations?), one can see who a project has ultimately benefited. And some simple rules of thumb also were expressed: “are black folks loving it?”.

A second set of questions asked how do you assess a project once it’s complete with answers that went beyond the simple idea of doing a post occupancy evaluation. Ideas such as creating place based “ambassadors” for a project as well as checking in at regular intervals (such as 6 months, a year, two years, and so on). There were many other ideas such as holding events with opportunities to assess a project as well as allowing people to compare original goals with final outcomes.

And finally, reflecting back on a project offers chances to make sure that each effort informs new projects and that lessons learned are documented and applied to future work. There was a recognition that universities often have short attention spans on projects they are involved in and to plan for this. And finally, making sure that anyone involved in a project (such as students) are properly recognized for their efforts.

Conclusions

Within each of the prompts were many clear and thoughtful suggestions for methods that can be applied towards publicly engaged projects. As the overall prompt was “rituals of repair” we might ask, in what ways are publicly engaged projects repairing or not repairing the places that they change or seek to change? All of the responses helped underscore this fundamental question and speak to the complex socio-political and environmental dynamics of place-making. Ideas that re-emerged in every section (before, during, and after) also underscored the need to consider who is benefiting from a project and who ultimately gets to represent it. And similarly, that reflecting on best practices is something that needs to be applied from project to project and shared and re-shared amongst audiences both local and beyond.

If you have additional thoughts or suggestions, or ideas for initiatives you’d like us to consider, please share with us. And we hope you’ll join us at future CoPED events.

-The CoPED team

Event Credits

SCAPE

Small Center

CoPED