Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership Case Statement

Christopher P. Long, Dean of the College of Arts & Letters and Dean of the Honors College, Michigan State University

Cara Cilano, Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, College of Arts & Letters, Michigan State University

Sonja Fritzsche, Associate Dean of Academic Personnel and Administration, College of Arts & Letters, Michigan State University

William Hart-Davidson, Associate Dean of Research & Graduate Education, College of Arts & Letters, Michigan State University

Ryan Kilcoyne, Director of Marketing, College of Arts & Letters, Michigan State University

Ryan Frederick, Videographer, College of Arts & Letters, Michigan State University

Abstract

The Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership (CPIL) framework is designed to cultivate habits of scholarship aligned with the deepest values of our faculty and the articulated values of the University. Our case study demonstrates the limits of traditional models of scholarly evaluation and proposes a new framework that will empower higher education to be a catalyst for transformative change.

Project Narratives

Introduction

Their frustration was palpable. Junior faculty on the tenure track in the College of Arts & Letters at Michigan State University who had been hired to do transformative transdisciplinary work were encountering obstacles at every turn. By the time they arrived in the Dean’s Office they had talked to supervisors and mentors, all of whom were supportive, but few of whom were able to clear a pathway for them to do the sort of meaningful work for which they had been hired. Their joint appointments were not working — there was little structure to ensure that the work they did in their transdisciplinary programs were legible to the faculty committees in departments that so often play a decisive role in determining who does and who does not receive tenure. When they finally had an opportunity to speak directly to the Dean, many spoke about the enormous amount of time they spent mentoring minoritized students — work they valued and very much wanted to do. They had been told, however, that this important mentoring work would not really count toward tenure. To make matters more disheartening, those who were spending time intentionally establishing relationships with local, regional, national, and international communities for participatory, community-engaged work, were being asked to parse this work into categories that pulled their holistic approach to scholarship apart. Our promotion and tenure framework was undermining the very innovative teaching and research we had recruited these members of the faculty to undertake.

Higher education stands at a crossroads. Traditional practices of scholarly evaluation remain entangled in individualism and a toxic culture of competition that fails to recognize the vital ways scholarship is enhanced and advanced by rich ecosystems of collaborations, from editors and librarians to community partners and mentors.1 Here at the dawn of the 4th Industrial Revolution and as the 6th Extinction presses upon humanity, higher education has failed to develop and enact institutional habits that will generate and support transdisciplinary, publicly-engaged, and intersectional ways of knowing capable of responding to society’s most intractable difficulties.2

And yet, a path forward may be discerned in the voices of a new generation of scholars who know how to engage and mobilize communities of action, are adept at transdisciplinary collaboration, and are unwilling to alienate themselves from the values that animate their most meaningful work. The path toward which they point requires higher education leadership to create and support policies and practices of scholarship that empower our faculty to put their core values into action.

A new framework

The Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership (CPIL) initiative is designed to cultivate habits of scholarship aligned with the deepest values of our faculty and the articulated values of the University. The publication, first, of our essay, “Staying with the Trouble: Designing a Values-Enacted Academy” on the LSE Impact Blog, and more recently, of our article, “Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership: An Initiative for Transformative Personal and Institutional Change,” in Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, demonstrate the degree to which this approach is gaining traction in the broader international community of scholars interested in the impact of academic research.3

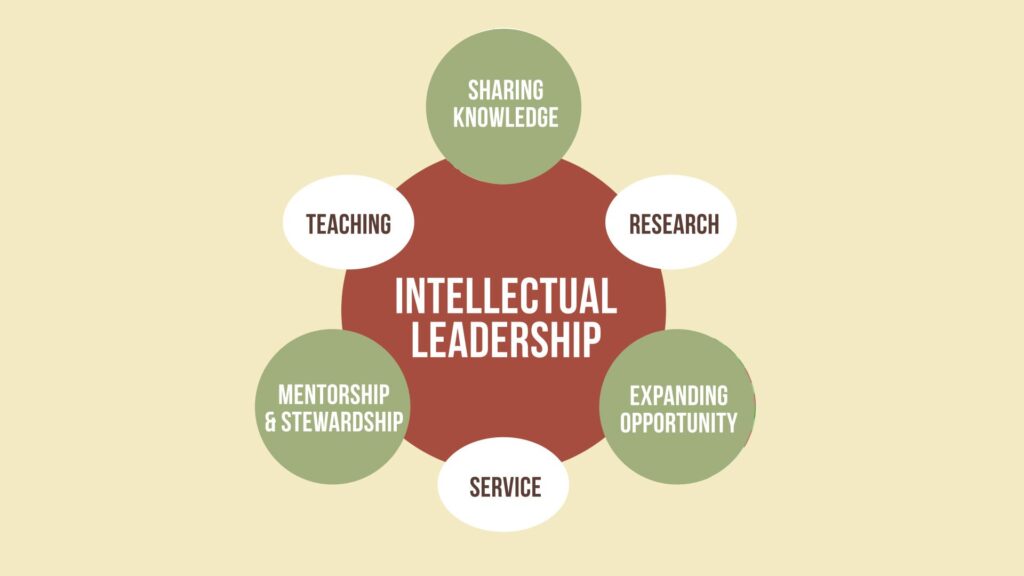

In these publications, we emphasize the important shift that the CPIL framework is designed to establish as we reimagine the tenure and promotion process as oriented not toward the activities of teaching, research, and service, but toward the broader ends to which our scholarly practices are aimed: sharing knowledge, expanding opportunity, and mentorship/stewardship.

To lend visual determination to the framework, we developed the following graphic, which is openly accessible on the Humanities Commons.

The semi-transparent circles in the diagram represent high-impact activities capable of enacting transformative change. The solid ovals identify the standard categories into which traditional tenure and promotion dossiers are divided. Research, teaching, and service — the traditional legs of the so-called tenure and promotion stool — are here recognized as possible practices through which scholars may pursue high impact achievements in terms of sharing knowledge, formal and informal mentoring, stewardship of institutional and environmental resources, and expanding opportunities for individuals and broader communities. The values that shape these activities appear in the background of the figure as the conditions that make intellectual leadership possible. The values to which intellectual leadership must hold itself accountable surround the graphic — intellectual leadership undertakes activities and achieves what it accomplishes in ways that are transparent, equitable, creative, and reciprocal. The framework is, of course, adaptable to different appointment types and employment categories. Faculty and staff are encouraged to identify the values that are most important to them and empowered to identify ways they might put those values into practice through advising, curricular reform, outreach, or through whatever categories their appointment identifies as standard.

The publication of the Staying with the Trouble essay was an early indication that the framework we were developing was gaining purchase in the wider academic community. Indeed, the shift for which we advocate was beginning to have a concrete positive impact on the faculty whose frustration and alienation had inspired the initiative in the first place. This shift opens new opportunities to recognize and reward a wider variety of activities as contributing to the core mission of the university. With the publication of “Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership: An Initiative for Transformative Personal and Institutional Change” in Change, we emphasized how the CPIL approach can expand to connect everyone who works at the university to its vibrant academic mission. As we discussed the framework more broadly across the College and began to encourage chairs to integrate the rubric of sharing knowledge, expanding opportunity, and mentorship/stewardship, into revised departmental by-laws and governing documents, we began hearing another kind of story—one of empowerment and care, in which faculty and staff were beginning to embrace the opportunities to tell more holistic and textured stories about the impact of their work across the three domains of high-impact activity articulated in the framework. The positive feedback we received from our junior faculty colleagues were not without their challenges, however. Structural and personal barriers remained, and many members of the faculty continued to express concern about the broader implications of fully adopting the Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership model.

Barriers to Change

Disciplines are policed at the department level, augmented often by expectations, perceived or real, adopted by national and international scholarly societies that reinforce traditional modes of scholarship and production. We found that even in contexts where the chair had fully embraced the CPIL framework, departmental-level annual review and tenure and promotion committees too often imposed regressive standards and expectations on dossiers that clearly demonstrated achievements in transdisciplinary and/or publicly engaged participatory scholarship.

This barrier is reinforced by academics’ acculturated habit of pointing to a higher level of the administrative hierarchy and announcing that “the Dean’s office expects…,” or, to the culture of the broader academic discipline:“in History, the University Press monograph is what matters most….” Too often these comments from committees or by well-meaning mentors reinforce a false sense of helplessness, as if faculty and our administrative colleagues are not ourselves the agents of the change we need.4 To be candid, we have had a difficult time convincing colleagues that the power to change review practices and criteria rests with them as they revise and develop formal documents like department bylaws and in informal ones like evaluation criteria/rubrics and charges to committees.

There are barriers to change within the ranks of faculty themselves, however much they might want the system to be different. Some faculty see this new approach as cumulative (more labor) rather than transformative (granting credit for unrecognized labor). There are cases where faculty members advocate for change through their own scholarship while simultaneously reinforcing existing practices because they expect the next generation of faculty to make the same sacrifices they had to make. This reinforces the importance of exposing more faculty to a broader range of interdisciplinary evaluation practices, so that alternate modes of assessment for the digital humanities, public humanities, film production, and the arts, can demonstrate the wide diversity of ways to assess the quality of scholarship.

Finally, the CPIL model expands the definition of success, making it less exclusive and elevating the standards for scholarship by facilitating a holistic review of scholarly practice. Those threatened by this shift attempt to equate this more inclusive and holistic approach with a reduction in quality, when in fact the framework recognizes high quality across a broader range of activities and practices than has been previously acknowledged.

Change became palpable only after trust was developed between the faculty and administrators, after chairs began adopting the model in departmental governing documents and practices of annual review, and after we began to see junior faculty earning tenure and promotion based on the framework itself. A major turning point was in the Spring of 2020 when seven of the nine faculty who were granted tenure and promotion to Associate Professor in the College of Arts & Letters were faculty of color doing innovative public and transdisciplinary work.

Momentum was further gained for the initiative when the University approved the creation of the transdisciplinary Department of African American and African Studies after two decades of existence as a program. We are leveraging the CPIL model to recruit a new generation of innovative faculty leaders to the University to build the new Department and establish a leading program in Black feminisms, Black Gender Studies, and Black Sexuality Studies and to enliven work in the arts and humanities more broadly.

Key impacts

In addition to these structural and cultural changes in the College of Arts & Letters at Michigan State University, we are beginning to see a broader impact of the model across the University.

In the spring of 2021, Provost Woodruff distributed a new Statement on Faculty Promotion and Tenure in which she emphasized the need to expand our approach to scholarship and creative activity in ways that align with the approach developed by the CPIL model. This passage in particular speaks to the “regressive” aspects of tenure and promotion the CPIL model is designed to address:

“When tenure and promotion systems become regressive, scholarship is reduced to attributes of existing knowledge legitimized by those who have long held privilege. They then fail to imagine new possibilities in whose interest these systems were formulated (at best) and exclude new entrants into the systems who are most different from those for whom the systems were originally created (at worst). The intention of this memo is to invite the units responsible for tenure and promotion recommendations in the University community to engage in a new kind of thinking that establishes and values a new level of creation, invention, production, discovery, expression, and revelation about ourselves, our world, and our place in that world.”5

In addition, this document articulates the express expectation that faculty provide documentation of their support of the University’s core value of advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

“Because DEI are core values of Michigan State University, candidates should detail their DEI efforts, providing evidence of their activities and accomplishments in the context of research/creative activities, teaching, service, outreach, and engagement. Faculty should include evidence of their activities and accomplishments in DEI, as appropriate, when detailing information on relevant research/creative activities, teaching, and service in appropriate sections of their dossier. Faculty should describe how these efforts are interwoven and enhance all other areas of faculty accomplishment.”6

This is an explicit affirmation of how the university will enact its commitment to DEI. This document stands as a strong indicator that a values-enacted approach to promotion and tenure is beginning to take root and grow across the university. Change advanced at the provost level finds support in changes that have been successfully adopted and implemented at the college level. Strategic interventions like the adoption of the CPIL model have the capacity to transform institutions and, over time, the very culture of higher education.

The CPIL initiative creates a fertile space for units willing to experiment with new modes of scholarship and evaluation by providing cover, support, and assurance that innovative practices will be recognized and valued as they move from the College- to the University-level of review. Respect for disciplinary autonomy at the provost’s level gives the dean’s recommendation — particularly when it is aligned with that of unit leaders (chairs or unit heads) — a great deal of weight and influence. Resistance is encountered most frequently at the senior faculty level, where the language of “upholding the highest standards of scholarship” too often cloaks an aggressive and regressive policing of the disciplines. By re-orienting indicators of success for senior faculty away from their own scholarly accomplishments and toward the success of their colleagues and the units to which they belong, attitudes begin to change over time. Tying these questions to the annual review process and subsequent salary increases provides significant personal incentive to focus efforts on helping colleagues advance along their pathway to intellectual leadership.

The CPIL model provides a framework to support more public, engaged, and activist scholarship by empowering scholars themselves to take an active role in determining the trajectory of their academic lives. The framework is designed to provide the structure for meaningful dialogue between organizational goals established at the University, College, and unit levels and the personal goals of scholars as they seek to develop meaningful careers.7 The current model of promotion and tenure puts too much weight on organizational goals and insufficient emphasis on the distinctive objectives of scholars. Too often the result is that scholars need to alienate themselves from the values they care most deeply about in order to meet institutionally established markers of success. Ironically, the values most institutions profess to stand for — publicly-engaged research, transformative teaching, transdisciplinary scholarship — are not even themselves served well by the standard model by which we make tenure and promotion decisions. The CPIL framework opens a space, therefore, for the transformation of scholars and the higher education organizations created to support them and enrich public life. This transformation unfolds within the context of structured dialogues undertaken annually in which organizational and personal values, objectives, and indicators of success are identified and agreed upon as the pathway that will lead to meaningful success for both. Cultivating institutional and personal habits of annual reflection, adjustment, and accountability is the most challenging and potentially transformative aspect of the CPIL approach. Much work remains to be done to establish the rubrics, governing documents, and interpersonal skills required to integrate these habits and practices into the life of the university.

No major challenge we face as a society today can be redressed with integrity or sustainability without the arts and humanities. The CPIL framework cultivates values-enacted habits of scholarship that foster public engagement, transformative teaching, and transdisciplinary participatory research across higher education. By aligning the personal values of scholars with the articulated values of the University, the Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership approach positions more members of the university community in more places to put their values into action in ways that make the world more equitable and just.

1For a broader discussion of these issues, see the work of the HuMetricsHSS initiative, including Agate, Nicky, Rebecca Kennison, Stacy Konkiel, Christopher P. Long, Jason Rhody, Simone Sacchi, and Penelope Weber. “The Transformative Power of Values-Enacted Scholarship.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, no. 1 (December 7, 2020): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00647-z.

2Framing the current moment between the 4th Industrial Revolution and the 6th Extinction follows Rosi Braidotti, Posthuman Knowledge, 1st edition (Medford, MA: Polity, 2019).

3Cilano, Cara, Sonja Fritsche, William Hart-Davidson, and Christopher P. Long. “Staying with the Trouble: Designing a Values-Enacted Academy.” Impact of Social Sciences (blog), April 23, 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/04/23/staying-with-the-trouble-designing-a-values-enacted-academy/. Fritzsche, S., Hart-Davidson, W., & Long, C. P. (2022). Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership: An Initiative for Transformative Personal and Institutional Change. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 54(3), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2022.2054175.

4This was a theme we found in research undertaken by the HuMetricsHSS initiative in interviews of 123 faculty, staff, and administrators across the Big Ten Academic Alliance, see The HuMetricsHSS Team, Agate, N., Long, C. P., Russell, B., Kennison, R., Weber, P., Sacchi, S., Rhody, J., & Thornton Dill, B. (2022). Walking the Talk: Toward a Values-Aligned Academy. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:44631/.

5Teresa K. Woodruff, “2021 MSU Statement on Tenure and Promotion,” 2021, https://hr.msu.edu/policies-procedures/faculty-academic-staff/faculty-handbook/recommendations.html.

6Woodruff.

7In “Mapping a Mentoring Roadmap and Developing a Supportive Network for Strategic Career Advancement,” Beronda Montgomery articulates this distinction between organizational and personal goals as a way to establish the difference between advising, which is oriented to organizational goals, and mentoring, which is oriented toward personal goals. See, Beronda L. Montgomery, “Mapping a Mentoring Roadmap and Developing a Supportive Network for Strategic Career Advancement,” SAGE Open 7, no. 2 (April 1, 2017): 2–3, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017710288.