Past Harms, Future Visions

Nida Rehman, Carnegie Mellon University

Edith Abeyta and Nica Ross, North Braddock Residents For Our Future

Abstract

Past Harms, Future Visions showcases efforts to advocate for environmental and community health, and create openings for just urban futures in Braddock, North Braddock, East Pittsburgh, and North Versailles. It features the work of North Braddock Residents For Our Future (NBRFOF), a volunteer-run, grassroots organization challenging unconventional shale gas extraction and pollution in the region.

Project Narratives

“Neither tales of progress nor of ruin tell us how to think about collaborative survival.” A.L. Tsing,

“Stories are productive and world-making, shifting collective understandings to allow new possibilities to be enacted and embodied through cultural practices that make sense of life in toxic landscapes.”

-Vasudevan Houston

How can urban and architectural design pedagogies engage in interpretive, collaborative, and community-centered approaches to rethink design methods as forms of environmental justice storytelling?

How can environmental justice activists utilize urban and spatial design to envision desired futures?

How do we tell stories that weave together the complex histories, politics, ecological and material effects, modes of resistance, and everyday experiences of toxic systems to help shape better worlds?

These were some of the questions which spurred our collaboration. In a phone call in early January 2021, Edith, an artist and founding member of North Braddock Residents For Our Future (NBRFOF), and Nida, an urban geographer and an architecture professor at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), talked about how Nida’s urban design studio course might support NBRFOF’s efforts to advocate for environmental and community health. This conversation marked the beginning of our collaborative action-design-research project, which has resulted in an online exhibition showcasing NBRFOF’s efforts to challenge unconventional gas drilling while bringing together the conversations of students and community members about how they envision different futures.

Background

North Braddock Residents For Our Future (NBRFOF) is a grassroots group that came together in 2014 when an oil and gas company contacted local residents to lease their properties for subsurface horizontal drilling or fracking on the Grandview Golf Course in North Braddock.

In the economic crisis of the 2000s, hydraulic fracturing to extract natural gas in the Marcellus Shale region was promoted as an “economic savior.” The borough of North Braddock, like many industrial or “post-industrial” communities around the region, has suffered continuing

the economic and demographic decline since the collapse of the steel industry. At face value, this drilling proposal offered to alleviate some of the financial woes in a community with a relatively meager tax base. However, many residents expressed strong opposition and concerns about the environmental and health impacts of fracking within the residential community. North Braddock Residents For Our Future worked with the Borough to define zoning policy, and in May 2014, the North Braddock Council passed a new zoning ordinance prohibiting gas drilling at the golf course.

Soon after the defeat of this first fracking proposal, in December 2017, a New Mexico-based oil and gas company called Merrion Oil and Gas announced a proposal to build six fracking wells at the US Steel Edgar Thomson plant, which sits across the boroughs of Braddock, North Braddock, North Versailles, and East Pittsburgh.

Edgar Thomson was the first steel plant built by Andrew Carnegie in 1875 and then sold to US Steel in 1901. It helped usher in the rise of the steel industry in the early 20th century and spearheaded the growth of towns like Braddock, which had a population of 18,000 by the 1950s. But with the decline of the steel industry, alongside white flight and political abandonment, the town lost about 90% of its population. However, many of its Black residents remained essentially “entrapped” by racist redlining policies. In Braddock, along with North Braddock, East Pittsburgh, Rankin, and North Versailles, residents live with ongoing contamination from the obsolescent steel plant. This is the story of many frontline communities along the highly industrialized river corridors in the Pittsburgh region, and especially so along the Monongahela River valley (or Mon Valley), where three legacy US Steel facilities have created intersecting and multigenerational harms for the largely Black, and relatively poor, communities.

The US Steel / Merrion fracking proposal promised to expand this toxic legacy

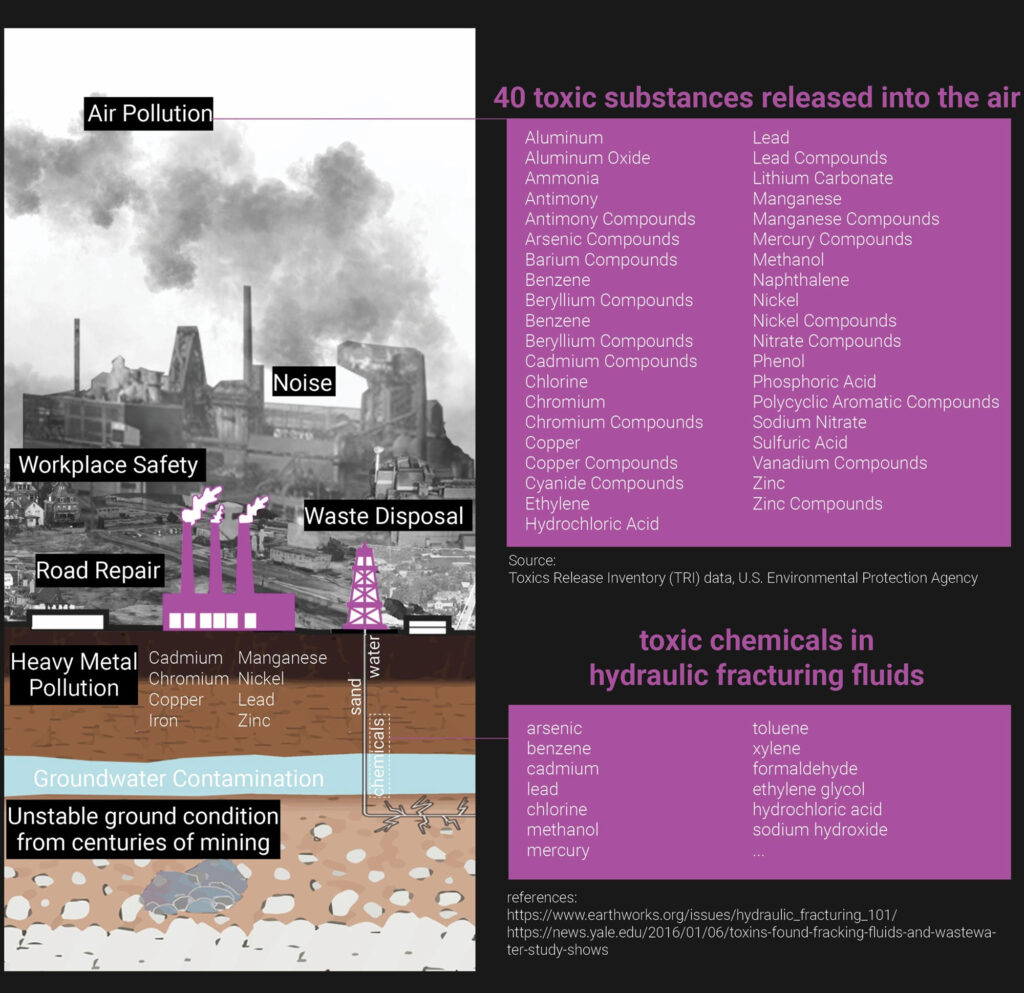

The environmental harms associated with hydraulic fracturing are well known, including the contamination of ground and surface water sources. Chemicals used during the fracking process — including arsenic, benzene, cadmium, lead, formaldehyde, chlorine, and mercury — are associated with developmental and reproductive harms. Humans may be exposed to these chemicals by drinking contaminated water sources, direct skin contact, or breathing in vapors from flowback fluids. Fracking sites adversely affect air quality, causing severe headaches, asthma symptoms, and other health problems. Fracking also increases the risk of induced seismic events, depletion of freshwater sources, noise pollution, and a range of workplace harms. The proposed drilling operations at Edgar Thomson would have added to the area’s extreme air pollution and other forms of environmental toxicity that these communities continue to face because of the steel plant — which has been listed as one of the ten most toxic air polluters in Allegheny County and has a decades-long history of clean air violations.

Once again, fracking proponents stressed financial incentives for the economically distressed boroughs and the steel plant as benefits of the proposal. While these initially drew in some of the local councils, the proposal was not met with silence. Residents of Braddock, North Braddock, and East Pittsburgh (led by the grassroots efforts of NBRFOF) mounted intense opposition to Merrion and US Steel’s plans. Over the coming years, this included organizing events and gatherings to raise awareness, encouraging residents to attend public meetings to express opposition, holding fundraisers to support legal efforts against the fracking proposal, and much more. As artists, members of NBRFOF leveraged their creative skills — alongside their persistent engagement with public policy, legal structures, and scientific data — to raise awareness about the dangers that extractive industries have created for local residents.

Objectives

In recent years, the environmental and social harms of extractive industries have been brought to light by activists and organizers around the region and visualized through a series of important projects and initiatives that range from documentary film, photography, 24-hour live–cam footage, real-time tracking of crowdsourced smell reports, fracking maps, and more. In our collaboration, we wanted to highlight not only these structural harms, but also the ongoing efforts and actions against these toxic systems. As artists and visual storytellers, members of NBRFOF have been working to build narratives around issues of environmental justice, intervening in dominant discourses around industrial and economic progress that center extractive industries. In an urban context long framed through the lens of boom and bust cycles, we wanted to experiment with modes of thinking and making that would “capture desire instead of damage” (Tuck, 2009). This meant bringing together materials that documented the ongoing histories of community stewardship and grassroots actions against the spatial and structural processes of toxicity while engaging community members in envisioning potential and desired futures.

Methods

Over the course of the semester, the seven students of Nida’s urban design studio (Jenny, Takumi, Lan, Siqing, Xinye, Schuyler, and Yi) engaged in dialogue with Edith, Tony Buba, Jan McMannis, Nica Ross, and other members of NBRFOF, as well as some residents of Braddock, North Braddock, and surrounding communities. Informed by these conversations, they used drawing, mapping, and design work to create a series of materials to visualize the histories and processes of fossil fuel extraction, industrial development, and environmental injustice. They also captured modes of community stewardship and residents’ visions for transformative change and just futures. These projects took the form of maps, timelines, sketches, collages, diagrams, and videos, all of which served as valuable tools and templates for collective thinking, gaining the trust and confidence of community members, establishing reciprocal engagement, and building relationships.

The remote modality of the collaboration was a challenge. Only three out of the seven students were based in Pittsburgh, with three in China and one in Seattle. Meanwhile, NBRFOF meetings were also being conducted online. We used online tools to manage the distance, this also created some unique opportunities for engagement and conversation. Some residents, who would have been otherwise unable to meet, could make space to chat over a Zoom meeting or phone call. Many times, sharing a screen — which revealed the messy, iterative, and responsive nature of the studio’s work (rather than completed presentation boards) — actually helped to facilitate dialogue and collective thinking. Meanwhile, Takumi, Jenny, and Siqing, the three students living in Pittsburgh, along with Nida, made visits to Braddock and North Braddock on occasion to meet outdoors with Edith, Tony Buba, Jan McMannis, and other local residents.

In these ways, our collaboration brought community desires, histories, and agency directly into classroom learning and pedagogy. It highlighted the need for students to understand and find ways to visualize how local debates about fracking were playing out in wider geographic and historical contexts; how power dynamics between state, corporate, and local actors become visible or invisible in efforts to promote or resist extractive industries; and how the area’s history of labor organizing and community revitalization continues to unfold in different efforts to build local power today.

Architectural and urban design pedagogy and practice have historically been framed around notions of individual (white/straight/male) authorship and mastery. Resisting these authorial impulses and conventions was a consistent challenge in the space of the studio. Moving between listening, talking, drawing, analysis, and reflection provided opportunities for students to think about how knowledge and action about the built environment are produced through everyday experiences and community expertise. Reflecting on this process during our final collective gathering for the studio on May 14th, Edith remarked on the “resident-driven” approach to urban design that had unfolded in the studio. She noted how, in contrast to community engagement processes which start with the visions and protocols of consultants, developers, or researchers:

Residents are here first. We are not responding to consultants that show up and ask us what we want. We’re in a situation where we’re working collaboratively with designers and youth and students, and people, you all, who have listened and heard us. You’re not saying, “this isn’t feasible, your idea isn’t feasible because there is not a market for it.” It allows this space and opportunity to actually have a dream.

The website

Over the summer, we began work on bringing these materials and conversations together in the form of a public-facing online platform that tells the story of NBRFOF’s campaign against fracking while situating it within a longer history, which includes the rise of the steel industry,

the ongoing transformations of the urban fabric in these communities, and most importantly, a history of local actions against environmental and social injustices. The site serves as an archive and resource for other activists, organizations, designers, and citizens, by making available many of the documents and materials from the campaigns against fracking at Grandview Golf Course and Edgar Thomson Steel Mill. finally, the site brings together many conversations and collaborations of students and residents about how they envision different futures for the community, despite, against, and beyond the legacies of toxicity.

Next steps

As we were wrapping up the studio component of our collaboration in April, US Steel announced that it had dropped plans for gas drilling at the plant. We celebrated this incredible victory of NBRFOF’s grassroots struggle and tireless organizing. While this is one step towards preventing additional environmental and human health harms in Braddock, North Braddock, East Pittsburgh, and surrounding areas, it does not mean that the fight for environmental justice is over.

Our hope for the website, and our collaboration more broadly, is to invite about the generative potential of design as a mode of environmental justice storytelling, which both “sets the stage for the exploration of potential futures” while helping to bring those futures into being (Houston and Vasudevan, 2017). Through this work, we also aim to intervene critically and productively towards institutional change at CMU — aligned with efforts to build architectural pedagogies centered on spatial justice, strengthen relationships with its wider community, and divest from the fossil fuel industry. Against modes of extractive institution-community relationships, our work also seeks to make space for scholars, designers, and students to be community allies — creating generative and supportive relationships. In the next steps of our collaboration, we hope to continue using collectively made drawings, multimedia materials, and local texts to draw out meanings, experiences, and possibilities within the urban fabric beyond the narratives of boom and bust and to create opportunities to enhance community health, ecology, and power.

1 Tsing, A.L., 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Edition Unstated. ed. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

2 Houston, D., Vasudevan, P., 2017. Storytelling environmental justice: Cultural studies approaches, in: The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice. Routledge.