Public Scholarship at the UCLA Community School

Karen Hunter Quartz, Director, UCLA Center for Community Schooling

Leyda W. Garcia, Principal, UCLA Community School

Abstract

The UCLA Community School was created to advance teaching, research, and service — merging the mission of the university with the core work of K-12 schooling as a university-assisted community school. It is an example of a public cross-sector partnership that contributes resources to K–12 schooling to study and support innovative educational practices that disrupt historic inequities in underserved communities of color. Housed on the former site of the Ambassador Hotel and one of six schools on the Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools campus, the UCLA Community School carries out the social justice legacy of the late Robert F. Kennedy. Kennedy’s long-standing friendship with Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and other civil rights leaders is memorialized in the school’s library — the former Embassy Ballroom — in a public art mural by Judith Baca entitled “Seeing Through Other’s Eyes.” Seeing through the community’s eyes is the approach that the school has taken to curate capacious spaces for public scholarship with a collective transformational stance that leverages the wealth of the community to nurture agency from a different baseline. Immigrant-origin youth, teachers of color, cross-disciplinary researchers, teaching artists, and many others produce knowledge that offers rich insights into how schools can transform our society.

Project Narratives

On his way to visit César Chavez in 1968, Robert Kennedy decided to run for President. He arrived in the rural California town of Delano to help his friend break a 36 day fast — a non-violent protest to improve wages, education, housing, and legal protection for migrant farm workers. Three months later, Kennedy addressed an ecstatic crowd in the Embassy Ballroom of Los Angeles’ famed Ambassador Hotel after winning the California Democratic presidential primary. The tragedy that ensued is well documented, but few have heard the remarkable story of hope and courage that lives today in the same space.

Now a stately library shared by six public schools — the Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) Community Schools — the former Embassy Ballroom is anchored by a 55-foot mural portraying Chavez and Kennedy at their fateful meeting. The mural watches over the education of 4,000 K-12 students, most of them immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Today, half of California’s young people are Latino. Only 18% of the adults in their lives are college graduates. The civil rights struggle of 1968 lives on in the proliferation of new public schools aimed at preparing first generation college-going students to succeed.

Our story focuses on one of the six RFK Community Schools — the UCLA Community School. Designed in 2007, our school was created to advance teaching, research, and service — merging the mission of the university with the core work of K–12 schooling as a university-assisted community school. It is an example of a cross-sector public partnership that contributes resources to K–12 schooling while studying and supporting innovative educational practices that disrupt historic inequities in underserved communities of color.

The library mural, Seeing Through Other’s Eyes, inspires our scholarship. UCLA artist Judith Baca shares the story of her mural with high school students in a seminar entitled “Art as Social Protest.” In this lotus blossom, she explains, each petal represents one of the issues facing society that Kennedy deemed most important: Environment, Intolerance, Poverty, Education, Health, and War. We see these things through different eyes: the eyes of a soldier, a woman and her ailing mother, a child in distress.

Seeing through the community’s eyes is the approach that the school has taken to curate capacious spaces for collaborative leadership that leverages the wealth of the community to nurture agency from a different baseline. Traditionally, educational institutions may not view local knowledge as a legitimate source of power, or even inspiration. Through our robust school-university-community partnership, we (as a school community) have the opportunity to redefine the project of schooling.

The people of the UCLA Community School are rich in cultural assets and knowledge, with intersectional and multifaceted identities. The school enrolls a diverse student body from the central Los Angeles neighborhoods of Koreatown and Pico-Union. The area is home to generations of families who migrated from countries such as Mexico, South Korea, Guatemala, Honduras, San Salvador, Nicaragua, and the Philippines. Most of our 1,000 TK-12 students are Latino (84%), 7% are Asian American or Pacific Islander, 5% are Filipino, 3% are African American, and 2% are White. Almost all (95%) of students report using a language other than English with their families. In addition, many families experience the challenges of poverty, with 95% of our students receiving free and reduced lunch. Most of the faculty are bilingual teachers of color, and they collaborate regularly with UCLA partners who serve as student teachers, teaching artists, tutors, community lawyers, researchers, and more.

Before the school opened, students as young as five endured long bus rides to more than 65 schools across the city. The dropout rate was high and less than a third of students went onto college. Now, more than a decade later, over 80% of students graduate and go onto college. Sebastian Hernandez manages UCLA’s Broadcast Studio and has mentored seniors each fall for the past decade. He teaches student interns the techniques and artistry of videography, while sharing his own story as a first generation college student. One year, he helped students produce a video about their alumni peers who were attending UCLA. He does it to open doors and advance justice.

A journalist visiting the school once called our campus “an oasis of multiculturalism.” Yet the oasis metaphor masks a deeper layer of meaning symbolized in the 26 murals that decorate the school — solidarity in the face of longstanding oppression. Above the entrance to the library stands Shepard Fairey’s 40-foot mural of Robert F. Kennedy and his words “Those with the courage to enter the moral conflict will find themselves with companions in every corner of the globe.”

Art has helped to define the school and strengthen its community. Students leading campus tours are quick to point out their favorite murals. David Flores’ City of Angels mosaic speaks to Wendy, a senior, who explains that it represents power and at the same time love. A recent controversy that erupted around the meaning of Beau Stanton’s Ava Gardner mural underscores the community’s engagement in this artwork.

A three-story mural of a high school student is overlaid with poetry: “I see you. I am you. We are one.” A student shares that she feels at home at the school: “None of us fit in the U.S. When we get together, we belong.” The UCLA Community School is a sanctuary school that strives to create trusting relationships and a strong sense of belonging. Immigrant-origin youth, teachers of color, cross-disciplinary researchers, teaching artists, and many others produce knowledge that offers rich insights into how schools can transform our society.

Three core beliefs guide our community’s scholarship:

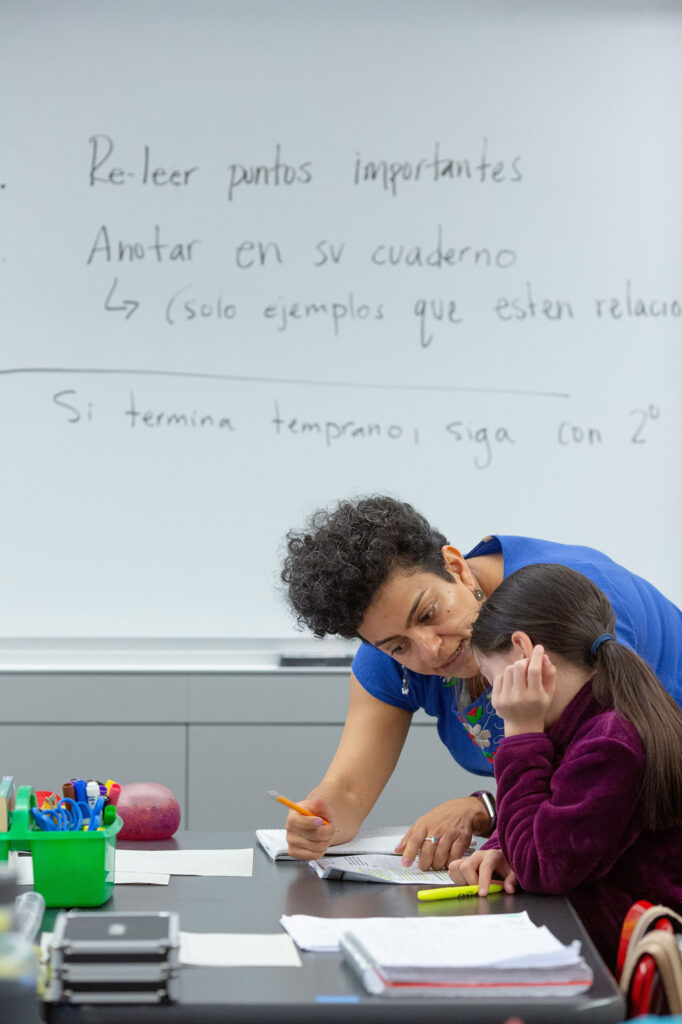

• Language and culture are central to learning and human development.

• Individuals learn as members of a community that values their participation and is respectful, productive, and inclusive.

• The purpose of schooling is to guide all learners, both students and adults, to think critically about the world around them, to engage as agents of social change, and to promote democratic practices.

Staying true to these beliefs takes an ongoing commitment to inquiry and dialogue that centers on the assets and insights of the local community.

We have had countless discussions and debates about what it means to advance justice through education. The global pandemic and racial justice uprisings have challenged us to think deeply about anti-racism and to adopt healing-centered practices. We have also set in place intentional structures to promote student agency. High school students have produced art and reflection on the meaning of justice. Elementary students express their identity and agency through artwork, play-based learning, and many other activities. Older students explore their passions in seminars and clubs, design their own research projects, and are encouraged to share what they know. As one student commented, “Teachers are very interested in learning from us.”

As a site of public scholarship, the school engages diverse voices in studying complex topics and generating insights and actions that improve the community. For example, we’ve collected biliteracy data over the past decade and created practices with teachers, students and families to analyze these data. Our dynamic multilingualism program now extends through 12th grade, and in 2021, 53% of the graduating class earned the State Seal of Biliteracy — in contrast to 13% statewide. Students embrace their multilingual identity and know that their language and culture are powerful assets that will help them navigate their futures.

The UCLA Community School was also created to be a Teaching School in partnership with Center X’s Teacher Education Program, assisting in the development of over 100 new social justice educators. When surveyed about their professional identities, 95% of our teachers agree that it’s important to read and discuss research and 70% agree that their professional identity includes being an educational researcher. Teachers take the school’s social justice vision to heart and many participate in community organizing and other networks outside of school. For example, Rosa Jimenez co-founded Reclaim Our Schools LA and serves on the district’s community school steering committee. Rebekah Kang leads the LA Network of Teacher-Powered Schools. And Jesenia Chavez writes poetry and produces a podcast: ¿Qué Me Cuentas?: Latinx Storytelling. Teachers bring their whole selves to school and to their scholarship.

In partnership with UCLA’s Visual and Performing Arts Education program, the school also prepares teaching artists within and beyond the school day. For example, the Multigenerational After School Arts (MASA) program engages creative artists from different generations in arts practice rooted in cultural traditions and issues facing the community. In 2016, after the federal election, MASA families created a sanctuary quilt that hangs on the wall inside the school’s Immigrant Family Legal Clinic. Inspired by this vision, UCLA law students learn and work alongside immigration attorneys to provide consultations, community workshops, and direct representation for students and families across all six RFK Community Schools. To date, the clinic has served hundreds of community members through community outreach events, one-time consultations, and direct representation.

Research on the MASA program highlights the transformative impact of culturally sustaining arts on individuals, families, and the school as a whole. As one parent reflected:

I have learned so much about myself by coming to MASA and I am proud of the artist I have become. So for me, it’s a second family, like a place we really fit in and belong. It is through art that our whole family and school has changed and become stronger.

This insight was captured (in Spanish) by Joselyne Franco when she was working as a research assistant at UCLA. A graduate of both UCLA Community School and UCLA, Joselyne is currently pursuing a master’s in public health to give back to her community — representing the transformational power of the partnership. As Joselyne shares, “I’m proud to say I’m first generation, coming to college, being low-income, but I made it. The American Dream is always this phrase that gets thrown around, but I am the American Dream.”

Joselyne is one of 719 graduates of the UCLA Community School to date. While 82% of these graduates enrolled in college immediately after high school, less than a third of the first two cohorts have completed college — signifying the enormous challenges first-generation students of color continue to face in higher education. Achieving the American Dream continues to be an uphill battle. Victoria Amador, who graduated from the school in 2016 and Cal State LA in 2020, participated in a research-practice partnership to understand how to help students persist through college. The study’s key finding was the power of community —of taking others with you. As Victoria shares: “As much as I have all this knowledge and I have my experience I’ve gained, what’s the point of having all of that if I can’t share it and support other people?” The idea of supporting her community and giving back is something she attributes to her family as well as the UCLA Community School’s social justice vision and tight-knit community. “It’s just the way that I’ve been experiencing life. It’s the reason I am who I am,” she says. Victoria advises other students: “Know that you are not alone. Share your challenges with people who can support you.”

On March 5, 2018, the children and grandchildren of César Chavez and Robert F. Kennedy joined students, parents, and teachers in the school’s Cocoanut Grove Theatre. They had all come together to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Chavez’s historic twenty-five-day fast in Delano — memorialized in the school’s library mural. Between the two men in the mural stands United Farm Workers cofounder Dolores Huerta, who stood by Kennedy at the podium in the Embassy Ballroom (now the school’s library) on June 5, 1968 — the night he was assassinated. On that spring day in 2018, to a packed and hushed audience, Ms. Huerta shared her experience working with both Chavez and Kennedy for the rights of farm workers and for social justice. She ended with a chant that felt suspended in time. Repeat after me: “Sí Se Puede!.”