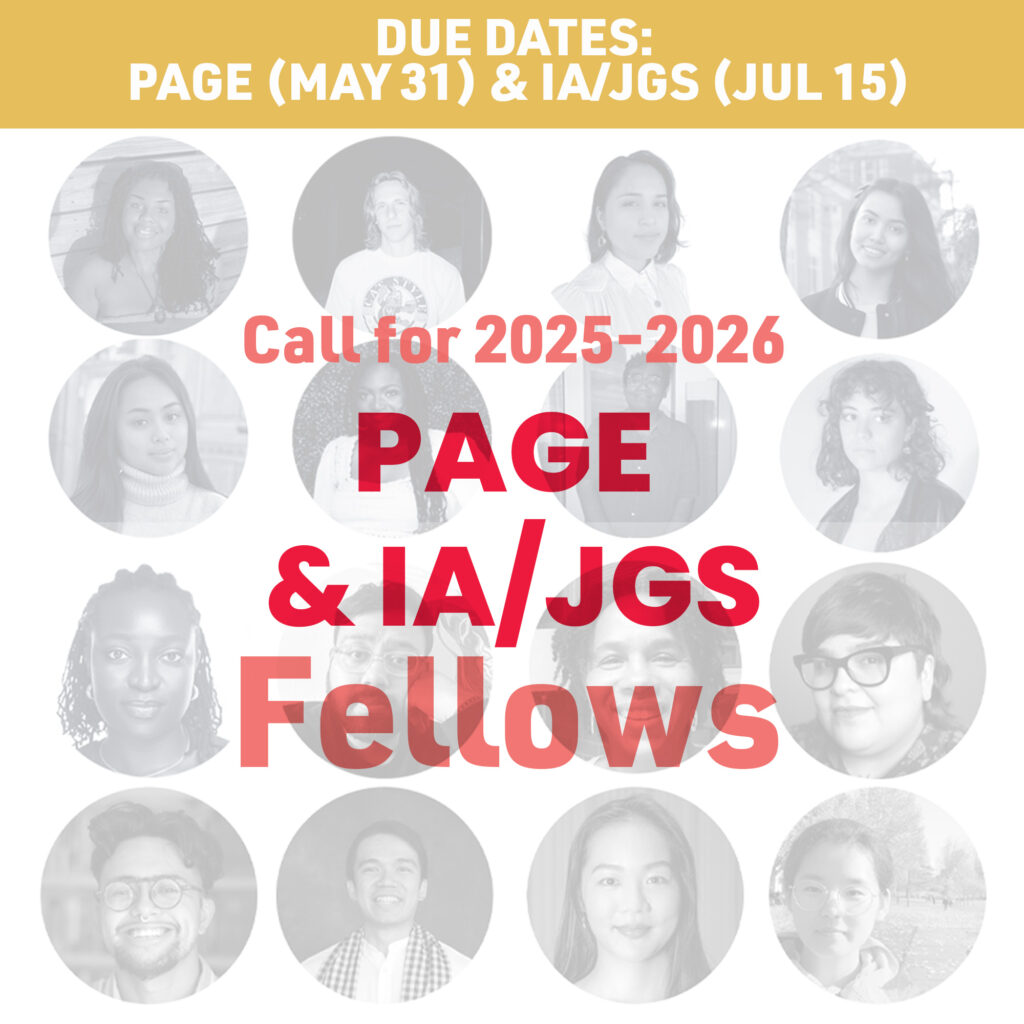

Race, Prison, Justice Arts

André de Quadros, Boston University College of Fine Arts & Prison Arts Project

Judy Braha, Boston University College of Fine Arts & Prison Arts Project

Krystal Morin, Boston University Prison Arts Project

Bradford Dumont, Boston University, Prison Arts

Alyssa Jewell, Boston University, MFA Student, College of Fine Arts

Abstract

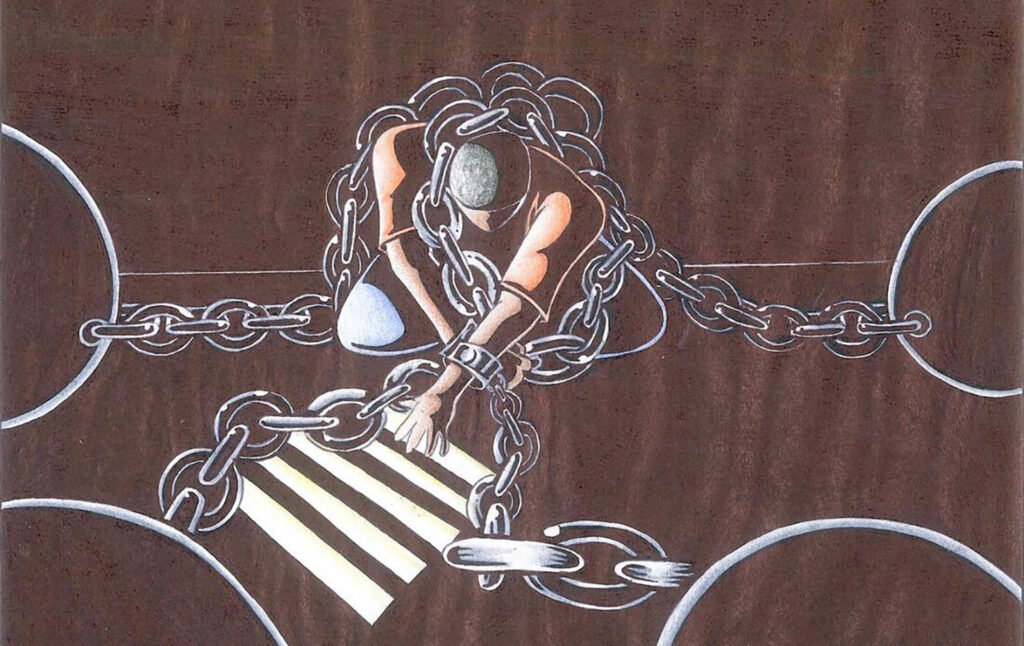

Race, Prison, Justice, Arts formed as an open dialogue sparking activism through the arts. We engaged a collective of undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, staff, and community members from varied programs across Boston University who participated in workshops or courses to explore race and the American incarceration system as a form of systemic injustice. With participants, we focused on the lived stories of Black and Brown incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals who have found expansion, personal discovery, and a path to activism through the arts. Throughout each experience, we presented special guests sharing first-hand accounts of incarceration through a variety of media including visits, written stories, artwork, poetry, phone calls, and interviews. Each artist’s story served as the catalyst for the creation of artworks that amplify the untenable situation in our country today. Through these experiences, we hoped to create common ground with participants from across the university, center and respond to stories of Black and Brown incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals, engage in creative play and collaboration that cultivates the students’ own voices, engage participants in responding artistically to injustice, honor and illuminate marginalized voices, initiate dreaming, visioning, and building together; and finally, to publicly share the fruits of the work made in response to arts as activism.

Project Narratives

To begin with, two stories:

The workshop participants were rapt. The miraculous had happened. Our incarcerated guest, the artist and activist Wayland Coleman, had called us from a medium-security men’s prison and gotten through during our workshop time. He was discussing how the arts and activism had changed his life. Participants were moved and hungry for more. Suddenly, a digital voice cut in: “You have one minute left.” Our guest kept barreling on, answering students’ questions, and then…click. Silence. His allotted 20 minutes was up. The group was stunned into silence. Bereft. For these participants, it was the most concrete example they had ever experienced what it is to lose one’s freedom. All the air was sucked out of our virtual room. We discussed our connection with and mourned our disconnection from Wayland and were able to imagine a small part of his reality viscerally. Participants were encouraged to create something in response to the experience of meeting him. We received and shared a flurry of poems, videos, and musical compositions at the next session — all in response to that one click.

Another story — our class met with Ras-Jahallah Shabazz (and his son, Jahallah) several weeks after Ras-J’s release from serving a decades-long sentence. Ras-Jahallah shared his poem “Children of War” with us, focusing on the plight of the kids who became victims of the War on Drugs — spending years and years disconnected from their parent(s). When students realized that Ras-Jahallah’s son, Jahallah (now in his late twenties, a toddler’s father), was four years old when his father was initially incarcerated, they were shocked into stunned silence. We all suddenly understood that this was the first year since he was a toddler that Jahallah had seen his father as a free man.

These events were two of many examples we experienced that emphasized the profound separation between human beings inside and outside prison walls. We came to this project with an intense desire to bridge that gap, to create proximity between them and us — not just as those incarcerated and not, but also between people of color and white people, the privileged and unprivileged. Race, Prison, Justice Arts (RPJA) sought to make us proximal to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals through deep listening and respect for their stories, experiences, and the humanity we share. We hoped to discover how we might instill the desire to listen with our hearts. We anticipated that our participants might feel destabilized and yearn for more layers of understanding in this process. For us, the questions became: In this disrupted and questioning state, how can we learn to activate ourselves? How can the arts become a bridge that enables us to engage our creative souls in conversation with this proximity?

Participants on and off the Boston University campus clearly had a desire to address issues of race, injustice, and mass incarceration after the intensely explosive summer of 2020 following the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many others at the hands of police. As faculty keenly interested in the arts and social justice with a decade of experience teaching in incarcerated settings, we also wanted to take action. We were interested in introducing students to the link between race and mass incarceration in the US and the power of the arts as a force for change inside and outside carceral settings.

RPJA formed as an open dialogue sparking activism through the arts. We engaged a collective of undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, staff, and community members from varied programs across Boston University who engaged in either a short-form co-curricular workshop or a semester-long course to explore race and the American incarceration system as a form of systemic injustice. With participants, we focused on the lived stories of Black and Brown incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals who have found expansion, personal discovery, and a path to activism through the arts. Throughout each experience, we presented special guests who shared firsthand accounts through class visits, written stories, artwork, poetry, phone calls, and interviews. Each artist’s story catalyzed the creation of new artworks that amplify the untenable situation in our country today. Through these experiences, we hoped to:

● Create common ground with participants from across the university

● Center and respond to stories of Black and Brown incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals

● Engage in creative play and collaboration that cultivates the students’ voices

● Engage participants in responding artistically to injustice and honor and illuminate marginalized voices

● Initiate dreaming, visioning, and building together

● Publicly share the fruits of the work made in response to their introduction to arts as activism.

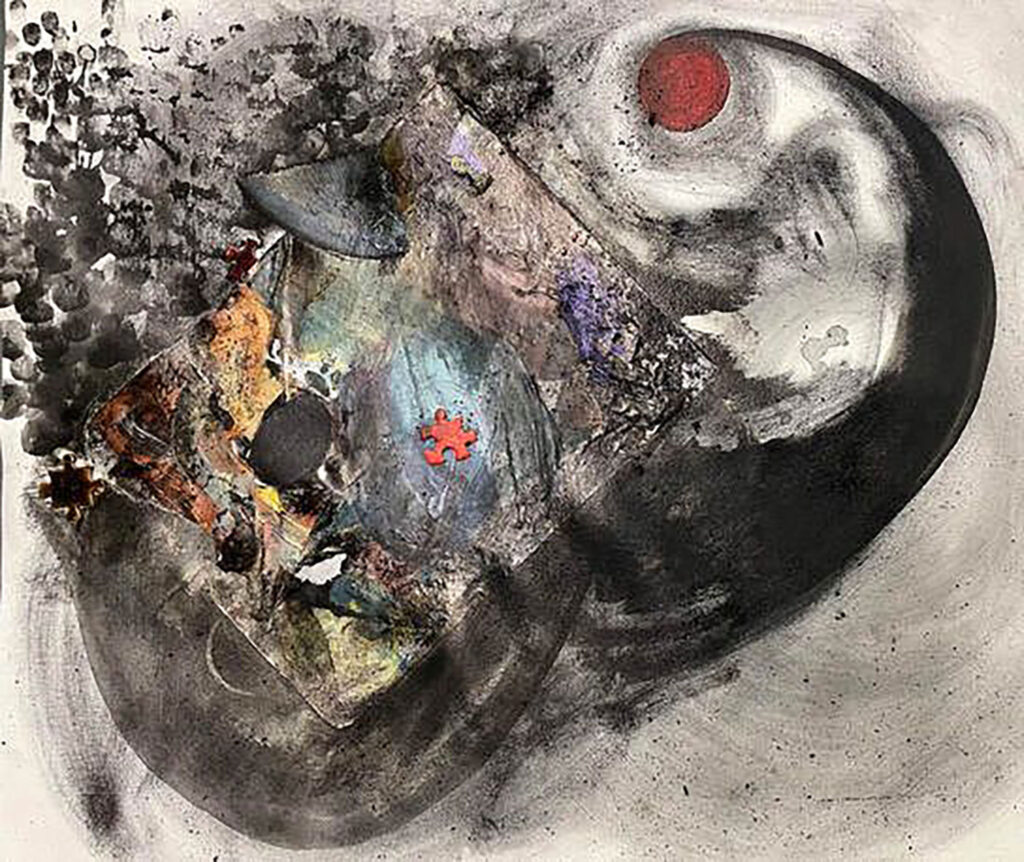

The culminating process of RPJA was the creation of a virtual public gallery that exhibited the creative work of currently and formerly incarcerated artists as well as that of our participants. Our participants shifted into an intensely collaborative effort to formulate a structure for the site and organize the work in a way that was easy to navigate and impactful to experience. We launched the gallery to the public at a virtual community event featuring some of our guest artists, community supporters, and participant voices to speak to the power of activism in the arts and what their big takeaways were in this process.

The synergy and alchemy involved in deep listening and artmaking, when fueled by empathy, can often revolutionize a person and transform misunderstanding into complete comprehension. Transformative methods in our project changed lives, opened hearts, inspired new forms of artistic expression, encouraged risk in creation, and open-mindedness, collaboration, and uplift.

This project was presented by the College of Fine Arts and supported by various departments and initiatives from Boston University, including the African American Studies Program, the Arts Initiative, the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground, the Initiative on Cities, and the Office of Diversity and Inclusion.

What kind of change or impact has your project/initiative/effort made?

For participants, the project has generated a new awareness and understanding of the prison industrial complex and its far-reaching effects by amplifying the voices of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists. This knowledge and understanding have particular power since the brutality of the carceral state significantly benefits from being unseen and unheard.

Large numbers of participants explored and expressed themselves through new artistic media and forms of activism. Strong bonds were forged during the process, and deeper connections with students’ humanity were cultivated through many methods, including reading, listening to each other’s stories, and creating to honor those stories. Partnering in fast-paced, collaborative assignments stretched participants creatively. In creating a living gallery that will continue to expand, this project will continue to generate new material and a space for students, community members, and the general public to engage and explore for years to come.

How does your work radically expand what we understand about who is a producer of knowledge, what the knowledge production process looks like, and what kinds of ideas and art-making matter?

Our work centers on those with lived experience in the carceral system, systemic racism, and the brutality of the legal system. Elevating and supporting their stories and engaging in live conversation and interaction have undeniable power. One of our formerly incarcerated collaborators, Ras-Jahallah Shabazz, shared, “…in a situation where someone wants to take a look at how your expression is, it’s also a form of listening. […] For someone to hear it and see them respond is a form of communication.”

We value an artistic process with intentional and empathetic listening and compassionate communication that fosters a positive and uplifting space for all (including those with diverging world views). Also, our work rejects the idea that only those with extensive training in a particular medium can be artists. We seek to empower all people to understand their artistic nature and to cultivate their unique voices and skills through play and collaboration in any medium. We emphasize the felt sense and avoid telling participants what to think, how to think, or delving too much into critiques and analysis.

What can other engaged scholars and change agents learn from it?

There is power in sharing truths about the criminal, legal, and carceral systems, racial biases, and longstanding injustices. There is power in sharing stories from individuals on “the inside” — in cultivating empathy, humanizing the incarcerated in the eyes of young people, and sparking interest in continuing to use the arts for activism. We have learned to make space for our guests to share what they want to say and engage in candid conversation about their lives and art. Additionally, we have learned not to be extractive or to expect guests to relive their past trauma. Creative project-based learning and human-to-human encounters are wildly impactful ways to approach this subject and this kind of work.

Conclusions:

Our process through the spring of 2021 taught us how the arts could become a bridge. This project illuminated the true value of educating participants on the facts surrounding historical and present realities of race and mass incarceration while allowing that knowledge to provoke committed activism through the arts. In bridging the profound separation between those on the inside and the outside through direct contact and engaging common humanity, a synergy was initiated through deep listening, empathy, and a path toward inspiring creation. Looking forward, we can envision future iterations of this project that will continue throughout this year and beyond. We look forward to participants continuing to work with us, initiating new projects as offshoots of our work, finding related paths to activism in careers, and growing our collective consciousness toward collaborative action through the arts.