Rebuilding Cornerstones: Toward Spatial Justice for Portland’s Black Diaspora

Karen Kubey, Assistant Professor, John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, Design, University of Toronto; 2019-20 Faculty Fellow in Design for Spatial Justice, University of Oregon

Kayin Talton Davis, 2020-21 Visiting Artist in Design for Spatial Justice, University of Oregon

Cleo Davis, 2020-21 Visiting Artist in Design for Spatial Justice, University of Oregon

Abstract

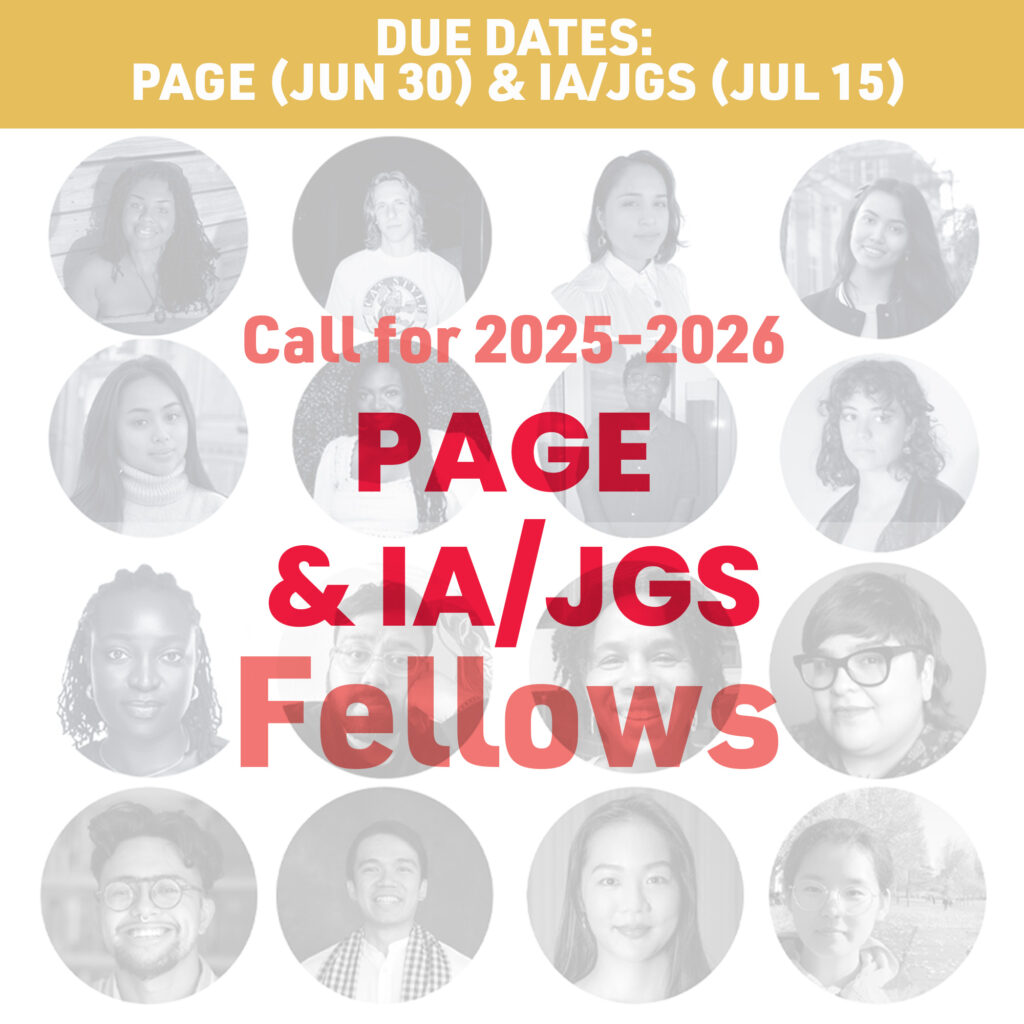

“Rebuilding Cornerstones: Toward Spatial Justice for Portland’s Black Diaspora” is a series of design studio courses at the University of Oregon (UO) that responds to dual challenges: for Black residents of Portland, and for the future of architectural education. Co-taught by Karen Kubey with artists Cleo Davis and Kayin Talton Davis, (and later by the Davises with Craig L. Wilkins), the series extends from the Davises’ long-term engagement with the historically Black neighborhood of Albina and with Black communities in Portland. Working with local youths, who joined us once a week in the studio, UO students created designs that combined new residential and commercial development with adaptive reuse of Albina’s historic Mayo House — now envisioned as the “ARTchive” for Black histories and futures. Students responded to community input and proposed speculative designs contributing to spatial and racial justice. The anti-racist design studio incorporated an Albina site visit, a field trip to the City of Portland Archives, a master class with representatives from UO Historic Preservation, and design reviews with community members and City officials.

Project Narratives

“Rebuilding Cornerstones: Toward Spatial Justice for Portland’s Black Diaspora” is a series of design studio courses at the University of Oregon (UO), responding to dual challenges: to support the Davis family and other Black residents of Portland, and to reenvision the future of architectural education. Artists and activists Cleo Davis and Kayin Talton Davis have been personally impacted by decades of disinvestment and unjust urban policies in Portland’s historically Black neighborhood of Albina. Most notably, in the 1980s, the City required the seven-unit apartment building that once stood on the family’s Albina lot to be demolished under Portland’s “Fight the Blight” policy, despite the Davises’ attempts to renovate the building. The family’s experience was common among Black Portlanders — “Fight the Blight” being one of several policies and interventions contributing to large-scale displacement and economic hardship.

The injustices that have occured in Albina and in BIPOC neighborhoods across the country are entwined with architectural education in the US, which has been largely Eurocentric and exclusive to elite students. This narrow approach to design training leads to negative impacts when students become practitioners. “There has been so much harm from design communities, whether it’s through intellectual theft or gentrification and condos going up,” Cleo Davis reflects. “There is this level of trust and respect that has to be made for the community.” “Rebuilding Cornerstones” confronts these parallel unjust legacies — in neighborhoods and in the classroom — through anti-racist, community-engaged pedagogy.

In the fall of 2019, UO Design for Spatial Justice Fellow Karen Kubey and the Davises, who became UO Visiting Artists in Design for Spatial Justice the next year, co-taught the first full “Rebuilding Cornerstones” design studio course in the series, identifying the historic North Portland community of Albina as the initial site of engagement. The instructors chose two sites to explore prototypical anti-displacement strategies — the Mayo House and the Historical Black Williams Art Project plaza. Working with local youth who joined the class once a week in the studio, UO students created designs that combined new residential and commercial development with adaptive reuse of the historic Mayo House as the ARTchive for Black histories and futures. They also co-produced designs for the plaza that would welcome youth and celebrate Black culture.

The “Rebuilding Cornerstones” series centers on the decades-long work of the Davises, Albina community-based artist-scholars. Weekly sessions with local youths offered a novel form of community engagement: Talton Davis used her high school teaching experience to devise short design exercises, offering UO students the opportunity to work side-by-side with young people aged eight to 20, co-developing drawings and models.

Students responded to community input and proposed speculative designs contributing to spatial and racial justice. The course incorporated an Albina site visit, a field trip to the City of Portland Archives, a master class with James Buckley and Skyla Leavitt from UO Historic Preservation, and design reviews with community members and City officials. The “Rebuilding Cornerstones” studio is a critical component of the University of Oregon Portland campus’s long-term commitment to spatial justice in the city. Spatial justice, a term coined by Edward W. Soja, refers to how social justice manifests in the built environment. Focusing on one specific community througfh multiple iterations over a period of time, the studio’s objective is to establish, deepen, and expand connections with local residents while working as partners to uncover, understand, analyze, and build proposals that creatively address decades-long systemic obstacles to the benefits of space and place.

Making Change in Albina and in the Classroom

Through diligent research as artists-in-residence at the City of Portland Archives and throughlongstanding advocacy, the Davises successfully fought to save the historic Mayo House and have the Victorian building moved to their family’s lot for future adaptive reuse — a story profiled in Ceclia Brown’s 2019 film, Root Shocked. Before the Davises saved the structure, the Mayo House was in disrepair and in danger of demolition to make way for condos. Its new location is the house’s fourth site, having been relocated twice before. It will now become the ARTchive, a cultural space for the Black community in “creating a place of memory, research, advancement, and art.”

Moving the house was logistically complicated and played out in public. As Talton Davis describes, “One of the biggest wins was the stories within the community that came from the move — people sharing how their families lost property, asking about how we were able to save the house, and what they can do with their properties. This was a major point of the move.” In addition to this feat, the Davises also achieved the rezoning of their property to allow for commercial development and new construction up to four stories in height. This paves the way for the kind of wealth-building opportunities that were denied the Davises, like many other Black residents, when their previous apartment building was torn down.

When Kubey joined the studio, visiting UO for a year from New York, she misunderstood where the young people were from. “At the beginning of the semester I thought, these are kids from Albina,” Kubey remarked. “It had to be explained to me that no, there’s been so much displacement. These are kids whose parents and grandparents are from Albina, but they don’t live there anymore, most of them.” The studio’s exercises gave the youth participants knowledge of their families’ histories, introduced them to the field of architecture, and allowed them to present designs for a Portland Black history plaza design directly to City officials, with the support of UO students. “For me, it’s about creating those spaces for cultivating Black joy,” Talton Davis says. “So often there is not space to have that joy, whether it’s emotional space, personal space, or physical space. How do you grow it? How do you make something that brings peace, where you are not wondering about neighborhoods being racist or you’re not worried about the city taking away your home? Working within the realm of spatial justice — it leads directly to that.”

Challenges

Engaging with local youth required overcoming significant logistical hurdles and was possible only through financial investment from the university. In addition to the pedagogical goal of bringing together designers of different ages and backgrounds, there were practical logistics — transporting young people to the UO building, gaining permission from their parents and schools, and providing them a pizza lunch each week. There were other challenges that would not be overcome during the term. Many of the older youth seemed to feel out of place, as if they didn’t belong in a university setting, or in talking about the future of their own neighborhood and city. Others had familial obligations that could not be changed, such as walking younger siblings home from school.

Eurocentrism and patriarchal, exploitative structures are baked into design education as we know it. European design is often held up as an ideal; a competitive atmosphere typically prevails in the classroom; and practices like all-nighters tend to be expected, or even encouraged. Working toward a more inclusive, liberatory pedagogy required carefully rethinking every aspect of the studio course to be welcoming, inclusive, and nurturing.

Sustained Investment in Engaged Scholarship

The ongoing series of Rebuilding Cornerstones courses taught by the Davises in collaboration with other Spatial Justice Fellows demonstrates what is possible with sustained investment and commitment on the part of the university. The courses are part of the University of Oregon Spatial Justice Initiative and UO Historic Preservation’s Albina Project, which asks how the field might support the preservation of Black culture in the neighborhood. Specific pedagogical strategies offer lessons for the design academy.

Notably, the studio rejected typical design reviews — the occasion for students to present their work publicly and engage in critical discussion — where juries are usually made up of architect-academics. Instead we invited multidisciplinary groups that represented a range of professional and lived experiences and centered Black Portlanders’ knowledge and visions. Architectural opinions were interspersed with stories from long lives spent in Albina, children’s interpretations of students’ drawings, and City officials’ responses to the work. As Kubey described, “In addition to typical architectural critique, we would have an eight-year-old saying, ‘Your roof looks like a bridge.’ The children’s perspectives were refreshing and as helpful to the UO students as the professional feedback.”

Reorienting the course around the perspectives of community members created a chance not only for local stakeholders to participate meaningfully: “It opened the doors to Black youth to say, ‘We belong in this space,’” Talton Davis noted. “As a result, UO students learned more about their own biases in a way that was truly personal. The structure of the course forced them to confront those feelings. This should lead to more creative and open design in the future.” The outcomes of the course, especially for the young people who participated, may not be fully known for some time. As Kubey observed, “I’d love to talk to some of these kids 10 years from now and see, did anyone become an architect? What’s going on? What are the impacts? We don’t know. We’re not going to know for a while what the impacts are in people’s lives.”

Centering the Lived Experience of Black Portlanders

Through design proposals combining architecture and historic preservation — all grounded in community histories and research — this series of courses seeks to contribute to spatial justice for Portland’s Black diaspora. Alongside community and architectural histories, students conducted research on real estate practices and city policies, examining historical patterns of disinvestment in African American neighborhoods. The series centers the lived experience of Black Portlanders from age eight to over 70, privileging very different voices than design education normally promotes. The studios have resulted in relational ideas and art-making, focused on responding to community input and (re)interpreting what spatial justice might look like.

One student’s studio project, “Higher Ground,” built off of the history of the site and surrounding community by unearthing centuries of Black prosperity and intergenerational knowledge. Another student’s “Afro Lab” provided a platform for Portland’s Black diaspora to envision their future alongside advancements in digital art and technology. The design process was as important as the products: by augmenting more typical site analysis with community-based research techniques, students created empathetic visual narratives inspired by an introductory tour through the neighborhood by the Davises, and through reading Karen J. Gibson’s 2007 essay, “Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000,” from Transforming Anthropology. Students pulled from Black design precedents — from Nubian approaches to Black Futurism — and developed drawings inspired by community perspectives.

The following iteration of “Rebuilding Cornerstones,” co-taught by the Davises with Belluschi Distinguished Visiting Professor and Faculty Fellow in Design for Spatial Justice Craig L Wilkins in the 2020-21 school year, took advantage of Portland’s new residential infill legislation and the network of the Albina Vision project, including the El Dorado architecture firm. In all, the work embraces the Davises’ belief that activist-inspired investigations are opportunities to combine independent design and development research with ongoing community input.

Portions of this case study incorporate information from the syllabus for “(Re)Building Cornerstones 2.0: Routes of Chocolate Cites,” 2020-21, taught by the Davises with Wilkins. Some quotes come from UO’s ‘(Re)Building Cornerstones’ Challenges Students to Unlearn Racist Design Practices and from the UO Design for Spatial Justice Podcast.