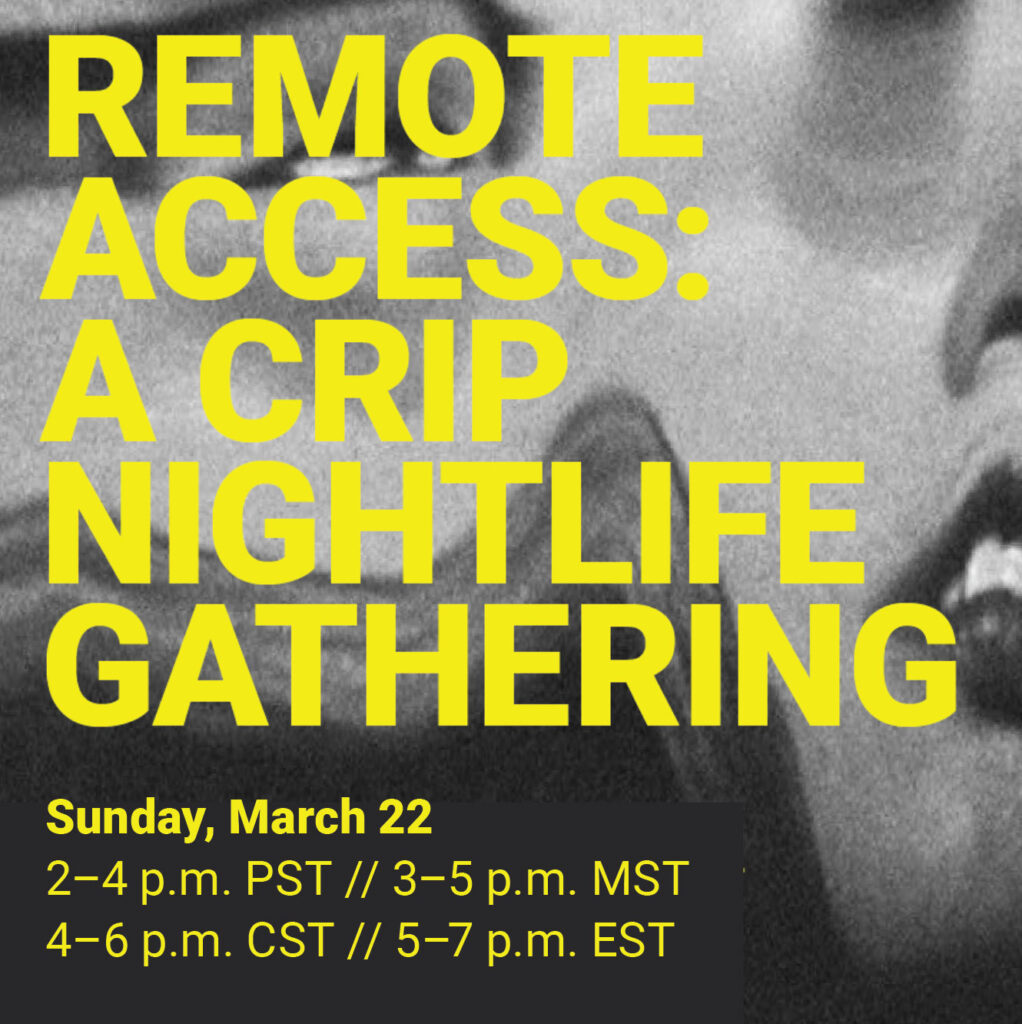

Remote Access: a crip nightlife

Aimi Hamraie, Associate Professor and Director of Critical Design Lab, Vanderbilt University

Kevin Gotkin, Disabled artist and DJ, Critical Design Lab

Abstract

Remote Access: a crip nightlife event emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic to showcase the innovative political work of disability communities in making remote participation possible. Using methods of accessible DJing, participatory image description, disability arts, American Sign Language interpretation, and live captioning, the events create an experimental space for access-making. This framework also builds on existing research and protocols created by members of the Critical Design Lab, a collective of disabled designers, artists, and researchers centered in disability culture. As options for remote participation dwindle despite the ongoing pandemic, Remote Access highlights the capacious social, political, and relational possibilities of disability-centered spaces that allow connection at a distance. In doing so, it highlights knowledge production and critical maker practices that are central to disability communities.

Project Narratives

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a quick shift to remote and online participation for many people in the U.S. Accommodations for remote learning, work, and telehealth became widely available. What was not clear to the general public, however, was that practices of remote participation have often been spearheaded, developed, and subsequently denied to disabled communities, especially communities of chronically ill, neurodivergent, Deaf and hard-of-hearing, Blind, and other disabled people. The Critical Design Lab, a collective of disabled designers, artists, and researchers, responded to the pandemic by offering a collaborative, digital social space to showcase remote participation within disability culture. “Disability culture” is the term we use to describe the practices, technologies, and relations that form in spaces that de-center ability and health as norms. As disabled artists, designers, pedagogues, and researchers, we carry forth the skills of disability culture during the pandemic. We pivot quickly and creatively when challenges arise due to format or space; we imagine long-distance participation as an opportunity to inquire about the values of comfort, slowness, and interdependence; and we draw on historical research regarding how disabled people and communities have utilized remote access since before the pandemic to shape our experiments in contemporary remote participation (Gotkin 2019; Hamraie 2017). In other words, our individual lived experiences of disability form a collective knowledge base, which shapes how we design, hack, and use technologies of remote access to form more convivial social spaces and relations.

Remote Access: a crip nightlife event is a quarterly online dance party and social gathering hosted by the Critical Design Lab and an emerging collective of organizers who utilize participatory methods of accessibility-making from disability culture. The project is a form of “research-creation” that centers disabled ways of “knowing-making” (Hamraie 2017), which are often devalued or decentered in decision-making about pandemic policies. Disabled peoples’ knowledge about design and the built environment is often undervalued; yet, we are keen observers and interveners in existing built arrangements. Remote Access builds on this direct, personal knowledge and collective knowledge. As a research-creation project, it also builds on our scholarly research about histories of disability nightlife (Gotkin 2019), disability-led design and crip technoscience (Hamraie 2017; Hamraie and Fritsch 2019), and an emerging archival project on remote access technologies before and during the pandemic (The Remote Access Archive, n/d). The event also utilizes methods that we developed in earlier projects, such as disability culture DJing led by Kevin Gotkin during nightlife community organizing in New York City in 2018 and 2019, participatory methods for accessibility-making (Hamraie 2018), and methodologies of “crip ritual” (Hamraie, Hartblay, and Moesch n/d). Furthermore, it expands on existing disability access protocols for collective and “participatory image description” (Kudlick and Schweik 2014) and “alt-text as poetry” (Coklyat and Finnegan, 2020). These methods have emerged from disability arts communities to provide information about visual content for users who are not sighted or neurotypical (among others), and to produce this information in a collective manner that incorporates the aesthetics and culture of disability. Combining these and other methods, Remote Access sought to create a space for showcasing disability cultural knowledge and survival tools for collective thriving, particularly tools based in joy and pleasure, to provide connection and healing during a time of fear and isolation.

Party-making in several iterations

Access is an always-incomplete project: no matter our intentions to provide maximum inclusion, there is always space for editing and further developing our practices. This approach to access as an unfolding phenomenon, rather than one made objective and stable by checking items off a list, is central to disability cultural approaches of making and doing. In formulating Remote Access, Critical Design Lab used an iterative process of theorizing, researching, designing, enacting, and revising/redesigning — an ongoing process.

Remote Access events take place on video platforms such as Zoom, and (more recently) 3D online spaces such as Arium. Using these technologies, the party series has been iterative, with each event building on the lessons of the preceding parties to produce new practices and solutions. The first party took place on Zoom in March 2020. The invitation included a participation protocol (Gotkin, Hickman, and Hamraie 2020), as well as an outline of procedures and practices for the party.

The Remote Access party protocol explained the party activities. If typical activities at in-person gatherings include chatting, dancing, listening to music, or eating, the means of participation in Remote Access are forms of interaction centered around creating access together as a collective endeavor. There is a live DJ set (typically presented by Gotkin, also known as DJ Who Girl), live real-time captioning, live audio description of visual content, and American Sign Language interpretation. These forms of access labor (Hickman 2019) are performed by practitioners with training — for example, in sign language interpretation or stenography — and most are hired by the party or offer their services pro bono. On the screen, disabled artists often show their work while participants produce image descriptions or describe the aesthetics of the music. At our first party, for example, moira williams (a disabled indigenous artist) and Yo-Yo Lin (a disabled Taiwanese-American multimedia artist) showed their visual and performance art. Using the chat feature, participants were invited to engage in “image description” and “sound description,” two disability culture methods for improving access to aesthetic content. They could also use the chat to socialize with other participants. A separate Zoom phone line was available with live audio descriptions of the images for those who preferred that method of receiving the information.

Throughout the event, a team of “access doulas” helped to coordinate technology, provide needed forms of accessibility, and assist participants in navigating the space. The role of the doulas was inspired by organizations such as What Would an HIV Doula Do?, which have been expanding on the crucial cultural work that birth and death doulas perform to aid individuals and communities through transition (Mahoney and Mitchell 2016). From this early access doula work, a network of access organizers has emerged that continues to hone practices for later parties.

At our first March 2020 party, nearly 200 participants joined over the course of two hours. Throughout the event, we marveled at the ease with which disabled community members entered into and shared the space. Participants also shared the access challenges they experienced, such as with the sound or the screen, and solutions were devised collectively.

News of the party spread rapidly. The party and its protocols also began to shape emerging scholarship in disability studies. Scholars Faye Ginsberg, Mara Mills, and Rayna Rapp (2020) wrote of the party in their essay “Lessons from the Disability Front: Remote Access, Conviviality, Justice,” noting the event and related disability cultural projects embodied “the reinvention of the political sphere to come.” Related gatherings also used the party protocol to facilitate other disability culture social spaces.

After the first party, Critical Design Lab gathered feedback from participants and grew the network of access doulas. This network reflected on knowledge and experience with the first party, as well as each person’s experiences with disability culture, to further develop accessibility practices. At the same time, Gotkin, working with disabled artist and researcher Louise Hickman, devised ways to “hack” Zoom to incorporate further accessibility features. For example, they figured out that the language translation channel on Zoom (which could be used, for example, for Spanish voice-overs) could be used as an audio description track. The benefit of using this track is that it would play over the music, rather than instead of the music.

After the March 2020 party, we curated several new iterations of Remote Access. A second party in July 2020, titled “Remote Access: Witches ‘n’ Glitches,” took place during the online Allied Media Conference. The party centered the concept of “crip ritual” alongside disability artists’ explorations of the “glitch” as an aesthetic and political form, connoting failure and disruption rather than smooth belonging. This approach aligned with methods of “access as friction” developed within disability culture (Hamraie 2017), often through design projects such as creating curb cuts with tactile paving or negotiating between participants’ competing accessibility needs.

With a party theme centered on magic, at “Witches ‘n’ Glitches,” a ritual invocation connected participants across distant spaces. A lineup of disabled artists offered visual art, danced from their beds, and invited participants into the practices of describing images and sound. An American Sign Language interpreter captured the feel of the music, in addition to the lyrics. A live captioner transcribed the lyrics and words said on screen. Access doulas guided participants through the use of the space. Whereas the first party had been populated by disabled people in our networks, the second party had a broader audience, including non-disabled people who may not have been familiar with disability cultural protocols. At the same time, nondisabled participants were invited to take part in accessibility protocols, perhaps for the first time. For many, the event was a gateway into disability culture; it demonstrated that disabled artistry is not just about identity politics or lived experience, but rather about layering the aesthetics of friction, negotiation, and interdependence.

As the pandemic continued, Remote Access protocols were used to host academic conference parties (such as the legendary yearly Society for Disability Studies dance — known for its celebration of disabled embodiments and styles of dance — and the Disability Futures Symposium, produced by the Ford Foundation with United States Artists and the Mellon Foundation), one-off celebrations (such as the anniversary of the journal Catalyst: feminism theory technoscience, which also published some of our scholarship related to this event), and personal social events such as birthday parties. In each of these events, the tools and practices of Remote Access found further articulation.

Another iteration of the party (“Remote Access: GlitchRealm”, April 2021) re-imagined the digital space beyond a Zoom screen. In one collaboration between Gotkin and disabled artist Yo-Yo Lin, the party took place in a three-dimensional participation platform called Arium, which operated simultaneously with the Zoom party. Gotkin and Lin designed the digital space to include multiple rooms, including an access doula hub, a dance floor, a karaoke room, and a quiet and playful space for viewing art by disabled artists (including born-digital and digital replicas). Avatars allowed participants to travel through the space and speak directly to other participants. Proximity to other avatars would amplify the sound, providing the feel of an in-person party.

Research-Creation and Knowing-Making

When it comes to disability and technology, disabled people are often treated as users, rather than knowers and makers (Hamraie and Fritsch 2019). As a result, the types of world-building that disabled people engage in can become imperceptible to non-disabled audiences. Yet, disabled people produce knowledge through various ways of designing and making in everyday life: from the need to hack a particular technology to suit a particular quotidian need, to the creation of new inventions for broader use in disability culture.

The history of disability nightlife reveals that spaces of leisure and sociality are also sites of critical knowledge production (Gotkin 2019). It may appear odd to characterize a party as a site of knowledge-production, but every aspect of Remote Access draws from and builds upon protocols, concepts, and approaches to knowledge-generation in disability culture.

Protocols for Remote Access further develop the existing practices of a collective of disabled artists and designers called the Critical Design Lab, which is based at Vanderbilt University and has membership in three countries and multiple time zones. The Lab, directed by Hamraie, runs remotely, using digital tools and platforms that change each year depending on the membership. The guiding framework of Critical Design Lab is the concept of “disability culture,” a term that we use to describe the technologies, practices, and relational possibilities that emerge when disabled people share spaces, whether digital or physical. Using remote access protocols, members of Critical Design Lab have run digital mapping projects, curated art exhibitions, produced a podcast on disability and design called Contra*, and gathered materials for an online archive documenting disabled peoples’ historical and contemporary remote participation. In shaping Remote Access, lab members also draw on their individual expertise, such as Gotkin’s DJ practice focused on disability nightlife in New York City, Hickman’s expertise in the politics of remote captioning technologies, and Hamraie’s experiences with community organizing in disability justice movements using livestreams and online meetings. These digital and humanistic projects work in tandem to offer scholars, creators, and activists a model for integrating knowing and making through a disability culture framework. We make protocols for each project available on the website (mapping-access.com) to enable the replication of and experimentation with our ideas. In the coming school year, the lab is also preparing a “Critical Access Primer,” which will build on key terms in critical studies of accessibility. These terms and concepts will then form experimental sites for further iterations of the party.

Remote Access also contributes new knowledge to non-disabled communities. One challenge of using methods from disability culture to curate remote social experiences is that not all participants may be familiar with these methods or identify as disabled. But as disabled activists, scholars, and designers, we are always in the process of documenting and showing these methods to broader publics, in the hopes that their adoption will improve the built-in accessibility of all events and meetings. In the case of remote participation, we wanted to highlight the existing work and protocols that disability culture had already developed in our frequent engagement in distanced relationality. Opportunities for using Remote Access as a space of aesthetic and political knowledge production emerged as the pandemic continued, making clear the stakes of continuing to hone remote access protocols, whether for work or social connection.

Within the context of disability community knowledge, Remote Access also serves as a testing space for critical approaches to accessibility, especially those that are intersectional and take power into account. A frequent debate concerning accessibility is the question of individual versus collective access (Lakshmi Pipeszna-Samarasinha 2018, Mingus 2010). Individual access is the model most commonly used in disability rights laws: individual citizens are empowered to bring forth lawsuits to enforce the need for a ramp or an elevator in a public space, but doing so does not change the broader environment or system. Collective access (Mingus 2010) is a contrasting principle from the Disability Justice movement and describes the efforts of disabled people to pool resources and knowledge in an effort to create access in less institutional and more relational ways. The Remote Access party is designed to enact collective access in real time between participants, highlighting a central principle of crip technoscience: “interdependence as a political technology” (Hamraie and Fritsch 2019). One critique of collective access, however, is that the mutual aid model does not account for the quality of access needed, and likewise does not compensate the access labor of workers with specialized skills and training. For example, community members with moderate fluency in American Sign Language may volunteer as interpreters, but they may not be trained to interpret to the standard needed by Deaf and hard-of-hearing people in the event, thus compromising access. Likewise, making access to images reliant on the descriptions of those new to the practice of image description may not ensure enough access. A challenge that we face with the party is ensuring the quality of access and compensating access labor while maintaining a commitment to community-centered mutual aid and experimental forms of accessibility — all of which may be emergent and imperfect.

As workplaces, including universities, reopen their doors within the evolving pandemic, the forms of remote access that made participation available for so many people are slowly being stripped away. We are finding that accommodations for remote teaching and learning are being denied at many universities, under the claim that such accommodations are unreasonable or onerous. Nevertheless, in claiming a participatory, digital, and remote party space as a site of protocol-generation and praxis, Remote Access radically expands typical understandings of disability when it comes to the use and design of technology. It highlights disabled users as designers, tinkerers, and hackers, whose ongoing practices of artistry and sociality coalesce in an archive of possibility: the possibility of spaces dedicated to access as an unfinished and aspirational project, enacted through ongoing organizing and community care.

Works cited

Coklyat, Bojana and Shannon Finnegan, Alt-Text as Poetry (2020), https://alt-text-as-poetry.net/assets/Alt-Text-as-Poetry-Workbook-PDF-2020-12-01.pdf.

Ginsberg, Faye, Mara Mills, and Rayna Rapp, “Lessons from the Disability Front” Contactos (2020), https://contactos.tome.press/lessons-from-the-disability-front/.

Gotkin, Kevin. “Crip Club Vibes: Technologies for New Nightlife.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (2019): 1-7.

Gotkin, Kevin, Louise Hickman, Aimi Hamraie, with the Critical Design Lab, “Remote Access: Crip Nightlife Participation Guide” (March 2020), bit.ly/RemoteAccessPartyGuide.

Hamraie, Aimi. “Mapping access: Digital humanities, disability justice, and sociospatial practice.” American Quarterly 70, no. 3 (2018): 455-482.

Hamraie, Aimi. Building access: Universal design and the politics of disability. U of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Hamraie, Aimi, and Kelly Fritsch. “Crip technoscience manifesto.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (2019): 1-33.

Hamraie, Aimi, Cassandra Hartblay, and Jarah Moesch. “Crip Ritual: Call for Submissions,” https://cripritual.com/.

Hickman, Louise. “Transcription work and the practices of crip technoscience.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (2019): 1-10.

Kudlick, Catherine, and Susan Schweik. “Collision and Collusion: Artists, Academics, and Activists in Dialogue with the University of California and Critical Disability Studies.” Disability Studies Quarterly 34, no. 2 (2014).

Mahoney, Mary and Lauren Mitchell. The Doulas: Radical Care for Pregnant People. New York: The Feminist Press, 2016.

Mingus, Mia. “Reflections from Detroit: Reflections On An Opening: Disability Justice and Creating Collective Access in Detroit.” INCITE Blog (2010). http://inciteblog.wordpress.com/2010/08/23/reflections-from-detroit-reflections-on-an-opening-disability-justice-and-creating-collective-access-in-detroit/.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Vancouver: arsenal pulp press, 2018.

Remote Access Archive. https://www.mapping-access.com/the-remote-access-archive