UnHomeless NYC

Midori Yamamura, The City University of New York Kingsborough Community College

Abstract

UnHomeless NYC is a group exhibition that brings together fifteen artists and artist groups who use participation, activism, and pedagogy as their media to examine the issue of homelessness. It was installed at Kingsborough Art Museum from March 7-April 14, 2022. Connecting students, artists, activists, academics, and the public, the show offered a forum to better understand New York City’s housing crisis and to think about our future as the city emerges from the pandemic. The exhibition is also an experiment in community-based teaching. 81.4 % of Kingsborough Community College students live close to campus on the southern edge of Brooklyn, yet most disciplinary-based curricula do not offer opportunities for meaningful community engagement. Our group thus selected to examine a housing insecurity issue in New York. Based on the 2018 #RealCollege survey, 55% of 22,000 City University of New York students were housing insecure in the previous year, and 14% were homeless. The numbers were higher in community colleges. Helping students understand how circumstances such as these can be reconsidered and addressed through the humanities can make their education seem more relevant to their everyday lives. In a redesigned course, ART 2400 (Global Contemporary Art History), students’ engagement increased by refocusing on artworks that address social issues, particularly projects that deal with housing insecurity. The success of this course made us realize that using such material is highly effective when teaching undergraduates who may be first-generation college students or are otherwise unfamiliar with using research to better understand contemporary life.

Project Narratives

Introduction

At Kingsborough Community College (KBCC), the majority of students do not write grammatically intact essays. In fall 2018, I encouraged students to compare two texts. Essay A an impeccably written autobiography of a girl growing up in a troubled family with her father abusing her mother. The writer researched and discussed statistics about domestic violence numbers in the United States and argued how her family was not an exception. The text urged readers to think about social ills hidden in plain sight. In essay B, the writer paid no attention to capitalization or grammar. It introduced the humble life of an adolescent who wants to live just a comfortable life with his dog. I asked students what they thought of the two essays. Everyone who spoke in the class supported B because B was more “real,” whereas A was written to “please teachers.”

If what professors consider excellent academic work is written to “please teachers,” then what type of work does a community college student feel is genuinely for them? Even if new to academic writing, students are eager to learn. My fall 2020 student, Eddie Saban, wrote: “Throughout the fall semester here at Kingsborough, I opened my eyes to many different things.” However, when Eddie decided to sign up for his art history class, he “thought I would be learning about the same old things I have been learning in art classes throughout my life.” For Eddie, the foundation of our higher education, or “elite knowledge,” is “the same old thing.” Nonetheless, he wrote: “I learned the most through my Art 24 class.”

So, how did Art 24 (Global Contemporary Art) differ from other art history courses? Art 24 focused on issues of housing insecurities, one of the topics that have become prominent in the New York art scene since the late 1970s. Like AIDS activism of the 1980s, art dealing with housing insecurities is bound to local community activism. While most disciplinary-based curriculum does not offer students opportunities for meaningful community engagement, in Art 24, I invited formerly homeless-housing-activist Rob Robinson to class. My student Eddie probably could relate to this class because the topic was closer to real life. Based on a 2018 #RealCollege survey, out of 22,000 CUNY students, 55% were housing insecure, and 14% had been homeless in the previous year. The number of homeless students was higher at community colleges. To improve the quality of humanities teaching and learning at community college, we situated ourselves in the community and explored community-based teaching, resulting in curating the exhibition UnHomeless NYC.

The Challenge

A pressing public issue we grappled with is housing insecurity. Housing insecurity is higher among community college students than four-year college students and is usually accompanied by other basic needs insecurities. In 2019, four professors from Art, Art History, Psycholinguistics, and Law and Sociology began looking into what causes housing insecurity. Rethinking the causes of homelessness was necessary. As one student, Amy Hernandez, wrote:

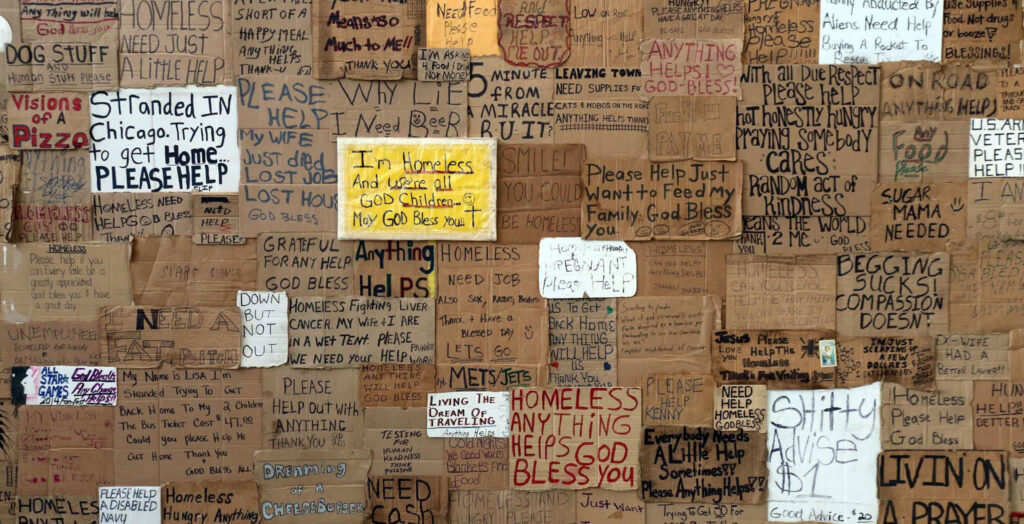

The news does not show you the homeless population that is disabled and has no family, the ones that were unfairly kicked out of their homes or the ones that have mental disabilities.1

Examining the homeless topic through art, analytical writings, and an invited speaker, our students learned to “understand the mindset of investors,”2 which could help remove the stigmas of being homeless. We thus established a research initiative, Unhomeless NYC. We implemented the topic of homelessness in Art 24, and students’ questions and concerns led to their search for solutions that resulted in the partially student-curated exhibition, UnHomeless NYC (March 7-April 4, 2022).

Milestones

To improve the quality of humanities teaching and learning at community college, we situate ourselves within the community. 62% of KBCC students are first-generation college attendees in their families and thus are often unfamiliar with how humanities research can contribute to the real world. In this community-based initiative, we created a course in which students could start thinking about how to contribute to their community using humanities skills. Such community-based teaching can make more sense at community colleges, as 81.4 % of KBCC students live in Brooklyn, and most of them commute from the Southern Brooklyn neighborhood.

When students watched the artist Miguel Robles-Durán’s Uneven Growth, a twenty-minute video about real estate in New York City, they began questioning how, “a 30-story, all-glass building across the street” might affect a “resident that lives in sub-housing.”3 Students were also “shocked by the fact that New York has more vacant spaces than homeless people.”4 Their curiosity led 9 out of 18 students who passed this asynchronous class to perform above the 90% grade mark. Moreover, the passing rate for ART2400 was 160% higher than in another asynchronous class, ART 37 — a survey of non-Western art. Students’ higher engagement in this course was because the topic was close to their everyday life.

Barriers

Despite the success of community-based teaching, courses based on problem-solving cannot enter into the CUNY Pathways curriculum — standard courses that yield convertible credits across all CUNY campuses. With almost no exception, these survey courses cram students with knowledge produced mainly by white male scholars. At KBCC, for example, the core curricula for art history requires students to study the extensive survey courses that cover prehistoric to contemporary art. Although professors have been making efforts to include more women and non-Western artists, there is little doubt that current survey courses center on European art, with 90% or more featured artworks made by male artists. These core curricula are usually uncritically accepted. By contrast, examining the real world through community-based teaching can develop alternative knowledge and expand our views of the world.

Together unfolding a local history, Manhattan Beach (where our campus is located), shows us how the area developed based on systemic racism. Here, certain racial and ethnic groups were barred from entry into the area. Such a history of discrimination contributes to how certain racial groups, especially African Americans, suffer from the housing crisis today. This type of microhistory could open up critical eyes in researchers and students and becomes an excellent opportunity to reexamine “official” histories of a place. However, such a de-constructionist approach can destabilize common knowledge — the same common knowledge currently taught as Pathways courses.

Impacts

Our project leverages the excellent collaborative environment between the humanities, social sciences, and STEM faculty at KBCC. We are proud of the interdisciplinary work that we accomplished with our UnHomeless NYC project, which includes humanities faculty co-teaching courses derived from common problems that we face in our communities. We now plan to develop our interdisciplinary initiative further with Be Here and Now!, an interdisciplinary research project in three interrelated topics that emerge from housing insecurity research. This project focuses on 1) urban poverty (housing insecurity and food insecurity), 2) recycling and zero waste campaign, and 3) land ownership and community gardens.

Students’ experiences with food insecurity are urgent at KBCC. Half of our students come from families earning less than $20,000 annually and thus are at a high risk of experiencing food insecurity during the economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic.5 In a recent study of the food insecurity experiences of 728 Kingsborough Community College students conducted between Fall 2019 and Fall 2020, over 53% of students reported struggling to obtain healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food regularly. Furthermore, students’ food insecurity scores were correlated with significant academic difficulties, worse health outcomes, less consistent access to health care, greater housing insecurity and incidences of homelessness, and worse psychological outcomes.6 Several campus-based food security programs can and do help students, as 44% of students reported at least one use of the campus food pantry and 32% reported at least one use of the campus Urban Farm. Our project, Be Here and Now!, leverages students’ experiences and interest in food insecurity to help students learn about and advocate for greater food justice on their college campuses and communities. By studying compost and reusable wastes at the farm, students will gain tools to develop ideas for an environmentally friendly future.

The KBCC Urban Farm (est. 2011) has traditionally educated students on food insecurity while giving them access to free organic vegetables raised on the farm. However, it was forced to close during the pandemic, with all of its staff members dismissed. It now seeks an academic rationale for sustenance, which we aim to provide. In addition, we plan to use the farm to explore communal land ownership and development. One of the issues that came out of UnHomeless NYC is the reuse of resources that could reduce income gaps and make the city more environmentally friendly. We plan to connect with the STEM faculty and look at compost and waste management as one way to think about environmentally friendly, regenerative future cities. All three topics, especially waste studies, can be developed into environmental studies courses co-taught with STEM faculty, which will combine humanities and science to open students’ eyes to a more holistic and sustainable way of approaching local systems.

By inviting community activists and socially engaging artists and examining problems inherent to our community, our project will help students to critically examine commonly accepted knowledge. More specifically, the housing crisis is deeply intertwined with racial issues in New York, so UnHomeless NYC can help students understand historical and contemporary issues related to civil rights and systemic racism in this country.

Homelessness is also bound to land ownership, which is the basis of capitalism. In the twenty-first century, in a world increasingly vulnerable to both an expanded economy and expended natural resources, we need to reimagine alternatives that can alter the private profit production-based capitalism. In our efforts to resolve homelessness so far, we came across the ideas of communal land ownership and recycling economy. Based on our principles to better society through education, we will further think from the ground up to propel toward creating a more environmentally friendly, habitable, and equitable world.

We use art and activism to deepen understanding of our community’s reality. UnHomeless NYC is transformative because the community-based teaching focuses on problem solving rather than rote learning. Through research and critical thinking, this project will alter the way we look at homelessness and make us reconsider the welfare of our future community.

1Amy Hernandez, response to Uneven Growth. 16 September 2020.

2Elizabeth McIntyre, response to Uneven Growth. 16 September 2020.

3Angela Small, response to Uneven Growth. 15 September 2020.

4Ryan Sharma, response to Uneven Growth. 20 September 2020.

5The 2016 Student Experience Survey. 2016. Accessed, 20 May 2021. file:///Users/midori/Downloads/2016%20cuny%20survey%20economics.pdf.

6 Ahmed, T., Ilieva, R. T., Shane, J., Reader, S., Aleong, C., & Wong, H. Y., & Chu, C. (under review). A developing crisis in hunger: Food insecurity within three public colleges before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition.