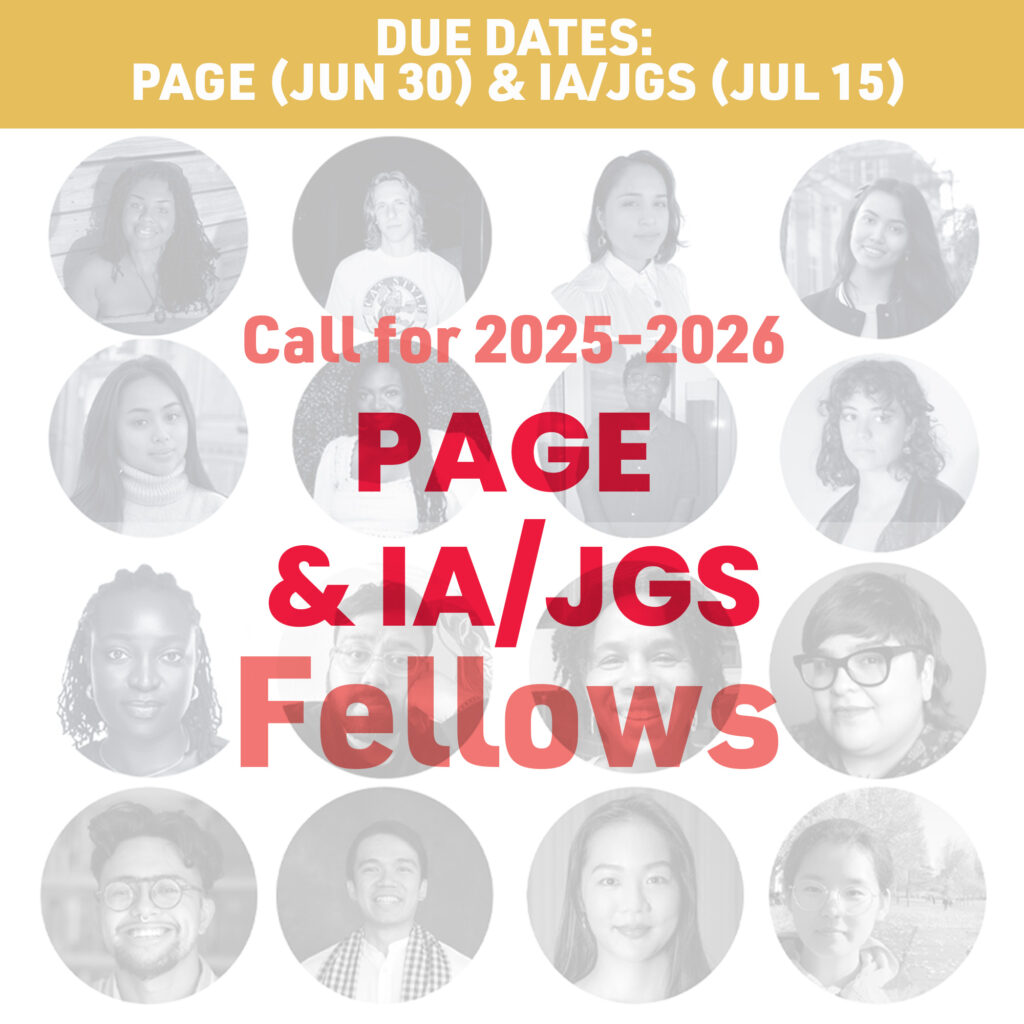

Yes, You Can: Artist Activist Creating Change

Diane Wilson, Executive Director, Michigan Artshare, Michigan State University

Petra Daher, Filmmaker, Petra Productions

Abstract

This case study features Michigan ArtShare’s collaboration with Detroit artist Chazz Miller. Precisely because our community engagement begins with a community-led approach, we have done powerful, collaborative work in Detroit that directly addresses the public’s need for art that challenges and inspires. Our project focuses on revitalizing the Old Redford neighborhood of Detroit and the newly renovated Obama Building at the corner of Grand River Ave and Lahser, just across from Artist Village Detroit, of which Chazz is a founding member. This building is called the Obama Building because of a mural Chazz painted and installed on the structure when it was dilapidated. That painting has been renovated and will hang as a permanent installation in the gallery that Michigan ArtShare will curate. Here, we showcase exactly the project that expands the ways in which academic institutions understand, value, and support public, engaged, and activist scholarship.

Project Narratives

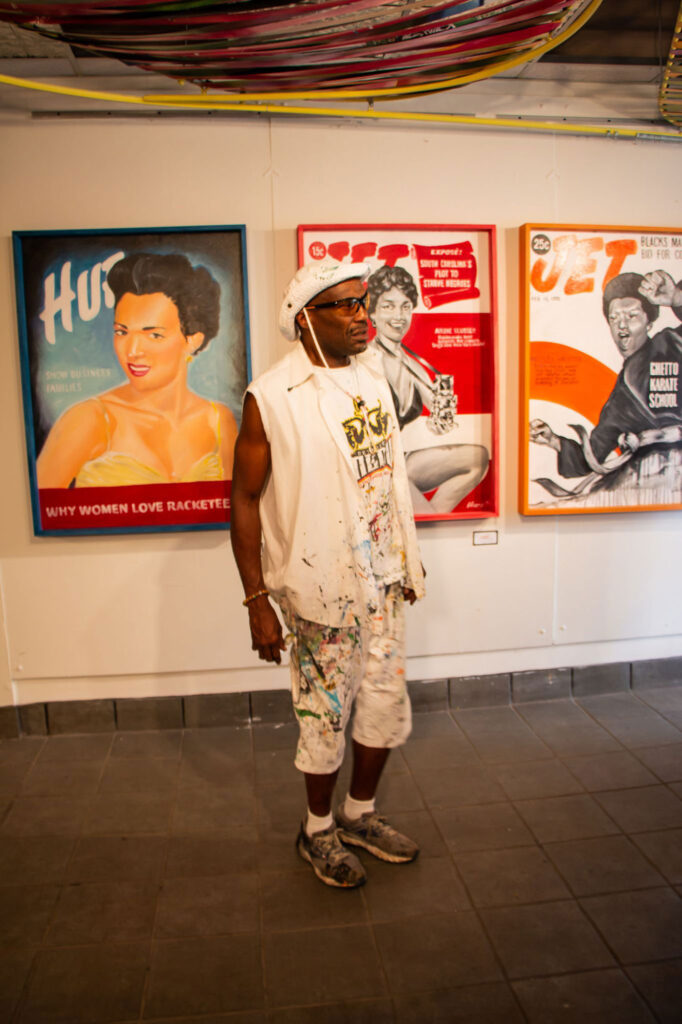

Charles “Chazz” Miller

Charles “Chazz” Miller is an internationally recognized street-mural artist, fine artist, and art teacher, born in Detroit in June 1963. Armed with his talent, Chazz traveled around the country, working as a graphic designer and fine artist. Some of his accomplishments include working for Stevie Wonder; Snoop Dog; MTV, and Warner Brothers Studios; producing live, ringside portraits of the George Foreman vs. Mike Tyson fight for Don King; painting celebrity portrait commissions; and producing two major fine art exhibits: The Canton Football Hall of Fame (1991) and an Exhibition of International Sports Media for the World Cup Soccer Tour (1994).

After returning to Detroit, Chazz traveled outside his neighborhood into an unfamiliar area, where he was car-jacked. At the time, he didn’t know he was in the Old Redford neighborhood near the building that would later become known as Artist Village, where he would eventually meet John George and Detroit Blight Busters. And so, it began.

Detroit Blight Busters

Old Redford has been a challenging Detroit neighborhood for the past four decades. The area was plagued by disinvestment by the city and developers and the resulting poverty, drugs, and violence. The people who lived there were frustrated and angry. Different things were tried, and one of those efforts resulted in the creation of Detroit Blight Busters, founded by John George.

Detroit Blight Busters gained the respect of local community members and city government by their relentless work toward the goal of making the neighborhood safe to live in. Blight Busters literally worked for decades with local families, neighbors, youth, and partners to create a volunteer powerhouse to address the immediate issues of drugs, violence, prostitution, and crime that so many in the community were struggling with and concerned about. Despite these efforts, without significant infrastructure investment in this neighborhood, these efforts seemed to be never-ending.

Artist Village

Chazz met John George of Blight Busters and worked for many years creating a visibly more engaging space in Old Redford, bringing his talent and energy to the table side-by-side with John George and other residents. This resulted in many public murals, and renovation of the buildings that now make up the Blight Buster offices, Java Coffee House, Chazz’s studio, classroom space, Farm City Detroit, and other spaces.

Michigan ArtShare first engaged with Chazz Miller in 2016 by hiring him to work with us on a public art street mural at another nearby community partner we work with, Roslyn Flint’s “Cross Pollination Corridor.” This partnership grew and deepened over time, leading to many projects in Artist Village and other neighborhoods in Detroit.

Creating Buzz

This higher visibility created a “buzz” around Chazz’s work. This buzz was significant enough to get the attention of funders and create a greater interest in how public art can transform a community. Artist Village was a physical space that could be visited and used as an example, and, finally, it drew the attention of a business investor with good intentions and the ability to follow through. Over the past 15 years, Blight Busters has invested over $300,000 in facility improvements to Artist Village. Today it is a 6,000-square-foot entertainment and shopping complex with five commercial tenants, three residential tenants, and two 750-square-foot office spaces.

This investment did not go unnoticed. We were not the only organization that saw the hope that Blight Busters and Chazz Miller were building in Old Redford. Meijer opened a retail store by tearing down the old high school and building a new supercenter on that site, which led to other businesses engaging. Peter Cummings of The Platform purchased three buildings nearby. One of those became The Obama Building. There are plans in motion for the other two.

Without the visible public art that Chazz created in Old Redford and the work of Blight Busters and local entrepreneurs, the neighborhood would have continued to struggle with a lack of resources and institutional support like so many other Detroit neighborhoods. With the right investment and the backing of people living in the community, Old Redford has definitely turned a corner and can look forward to a brighter and safer future.

The investment is in the relationships.

When the Detroit News covered the groundbreaking of The Obama Building, Michigan ArtShare was not in the headline or mentioned anywhere within the newspaper article: Detroit’s Obama Building reopens as home to businesses, affordable apartments (detroitnews.com). And it was a win for activist scholarship. Michigan ArtShare was not a central actor in this story. We provided a supporting role, and we did it in the way we purposefully structured how we work with any community. First, we are invited in. Second, we listen, then listen some more. Third, we work to support and guide projects to completion by providing personal support, access, opening doors, brainstorming concepts and solutions, and on-the-ground fieldwork.

We also worked in reverse order of what might be expected. Diane Wilson, Michigan ArtShare’s creator and executive director, placed herself in a role to support the project. Then Amy Wellington, a Michigan ArtShare program director (shown in the video working with Kev E Kev), spent untold hours listening, planning, supporting, assisting, and generally keeping the train moving.

Diane viewed her primary role to be one in which her job was to listen, provide insight and direction when needed, open doors, provide a stable infrastructure to work from, do a fair amount of editing and accounting, and generally make sure that Amy had what she needed to effectively support Chazz in realizing his creative vision. There are many moving parts to these projects, and absolutely nothing runs on time. There are many twists and turns and many problems to solve. We work on multiple projects in different parts of the state simultaneously, always with the same approach of being invited to listen, support, and collaborate, then bring our expertise and access to the table to help make the vision a reality.

Create collective opportunity.

When the pieces all come together, as they did in Old Redford, the community creates a solid base from which to rebuild. The positive results will reverberate throughout Detroit for the next 50 years and beyond. This revitalized business district will grow and provide stability necessary for the next steps to build upon. The opportunity was created and sustained by the community activists working on the ground, making their local vision a reality. The public art and classes created a vibe and a hub where other people could begin to see the possibility and engage.

Society often undermines people perceived as being of a certain class or economic status. People might not be taken seriously and can be presumed to be inept or not intelligent, perhaps viewed as having not much to offer. We challenge that view on many fronts.

People choose to live in a particular location and a particular manner for any number of reasons, many of which may not make sense to others. Some people, like John George, want to remain in the neighborhood he grew up in. Some people, like Rosalyn Flint, look for ways to make a community better, even if they don’t live there. Some people, like Diane Wilson, go back to their old neighborhood, and they want to find a way to be a part of revitalizing the area. Some people, like Chazz Miller, stumble into a neighborhood and want to use their talent to make an immediate difference and provide a vision for what is possible.

Support a community’s vision

People come to a project with a vision and a set of skills. Sharing those skills willingly and giving weight to the ideas of the people who actually live or work in the community now is the catalyst that allows a project to start and will sustain it through the complicated and winding path to completion. The vision of the community members must be supported. Only then can those involved help provide access to resources and open doors, people from the community through those doors.

We take more than one step back in every project and allow community members to guide the process. They know what they need and want in their community. Our job is to assist where we can, provide access to expertise when needed, and remember that we are all in this together.

How did activist scholarship identify and connect local artists and funders? Play a quiet role.

It is wrong to assume that the local artists don’t have important connections of their own. We might expect that they would have strong connections in their local community. We might find ourselves surprised to learn that some artists, like Chazz Miller, and some activists, like John George, have built connections with government officials and agencies, foundations, and other funding sources on their own over time. To go into a project assuming the academy is the most significant player in the room would be wrong. That is not the way we work. By respecting the education and experience of the local team, we move at a much more robust and faster pace.

In our daily work, we engage people at all levels of the academy, government agencies, and business. Our job is to find the connecting lines and make sure that everyone has access to the table as early in the project as possible. This can mean that multiple, simultaneous projects need to be supported. We must check our egos at the door. We must truly collaborate. We must genuinely respect the individuals we work with and the knowledge they bring to the table. It is our job to open doors and make sure everyone feels welcome. That can mean inviting the community to the university and into meetings that might look very different than what they are comfortable with. It can also mean inviting university officials to meetings that might be outside of their comfort zone.

It’s about how we did it, not what we did.

The example of Artist Village Detroit is powerful in that each entity involved came to the project in their way. Not everyone, or every organization, was involved in every area of the project. Everyone brought their strengths to the table and worked on their piece.

Michigan ArtShare saw its primary role as a creative partner to Chazz Miller, keeping him working, creating, and sharing his vision, so we could all understand our roles better. Chazz was the visionary and the motivator. His vision helped everyone: the developer, the city, and the community. It invited them to “see” what was possible and protected the space that allowed each entity to do their part and make Chazz’s vision a reality.

We would be remiss if we did not also mention that woven alongside the work at Artist Village, Chazz also needed to make a living. He continued with mural making and fine art sales in other parts of Detroit, creating community engagement murals in the Live6 neighborhood with Philadelphia Mural Project and earning a place in the Eastern Market mural exhibit with his tribute to Aretha Franklin, among other things. Amy Wellington worked side-by-side with Chazz to secure these projects.

There are many ways to signify that change is in the air and communicate that to the general population. One of the impactful things Michigan State University Extension did was hold their 2019 Fall Extension Conference in Detroit, inviting over 600 Extension employees from every corner of Michigan to spend three days in the city. This direct experience is invaluable to those educators and the faculty and executives they work with.

What engaged scholars and change agents can learn from us is how we did it, not what we did.

Chazz’s “First Dance” hangs as a permanent artwork in the Obama Building as a reminder to dream and share your dream with others. Hope is the best motivator.